The Home-School. Isn’t that a pretty name for a school? Now I want all the Pansies to listen while I tell them where this school is.

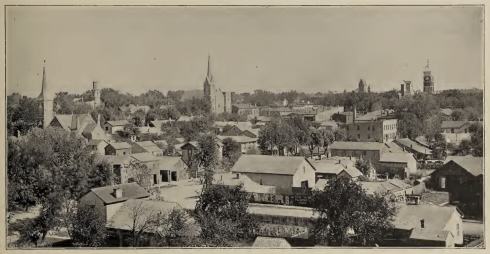

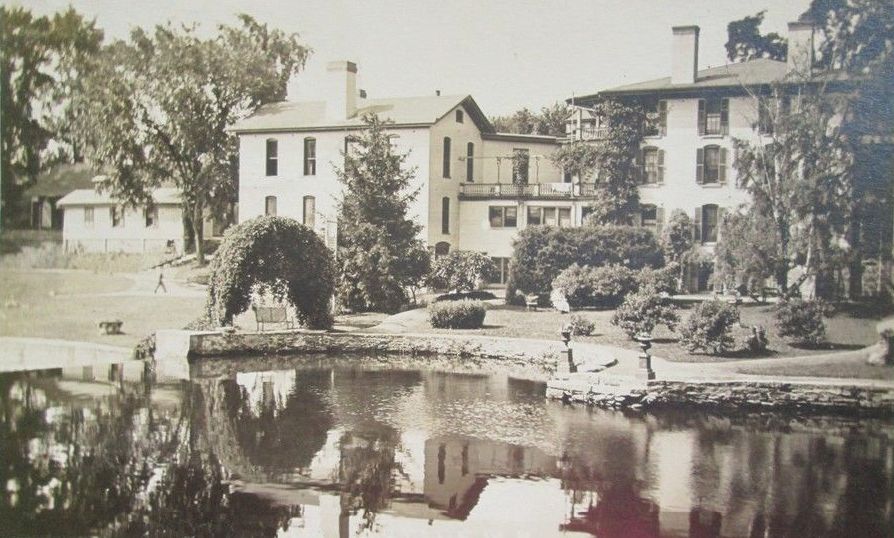

When you get to Utica, on the Central Railroad, you want to take the street cars that always stand at the depot waiting, and half an hour’s pleasant ride up Genesee Street—one of the prettiest streets in New York State—will bring you to New Hartford.

This is a pretty, pleasant village, just far enough away from the noise and bustle of the city, to give you sweet sights and smells, and pleasant country sounds.

A pleasant walk up the hill and you reach a home hiding among great old trees. You never saw a prettier yard than belongs to that house! Lovely little evergreen trees just starting into beauty, snuggling under the great giant trees that tower above them on every side. There are mossy banks, and grassy walks, and a lovely mound of grass, in the center of which plays a fountain. There is a winding graveled carriage drive quite up to the door of the house, and there are flowers, and shrubs, and ferns, and lovely grasses everywhere.

Of course the house hiding behind so much beauty is a large pleasant old house, with many unexpected rooms starting out where you thought there was only a door or, at best, a clothes press. In one of the sunniest of these rooms, the home-school gathers every morning at nine o’clock, some of them boarders, some of them day scholars, all of them happy and bright.

One day last week I peeped in on them. Someway, the pretty little tables covered with green spreads, and comfortable looking chairs standing before them, and the large old-fashioned lounge at one end of the room, and the pictures on the walls, and the flowers in vases everywhere, made this look unlike any other schoolroom that I ever saw. “The home-school,” I said to myself. “Yes, it is rightly named; it does look like a home.”

There is another reason why “home” is a particularly good name for it: there is a mother in it. One of those sweet and quiet women, who seem to be voiceless, where the plannings are concerned; who sit often in quiet corners, with knitting or sewing, while the bustle of life goes on; but who are, after all, the planners, the managers, the grand central wheels in the machinery of home life. Just such a mother is there; and to show you how all the scholars feel the influence of home, let me tell you that by tacit consent they have fallen into the habit of using the familiar “papa” and “mamma” to the heads of this household instead of the colder, more dignified names which are used in speaking of them.

Now let me tell you a bit of a secret. You know Faye Huntington? She has written many a story for us, you remember. Well, she is a power in this school; one of the teachers, one of the helpers, the friend to the scholars, the sympathizer in all their schemes, or troubles, or disappointments.

The mother there is her own mother, and the young lady teacher who is the principal of this favorite school of mine, is her sister; and they all, from first to last, are among the dearest, and most honored, and most precious friends that Pansy has in this world.

Now, why am I telling you all this? How do I know but you are looking out at this moment a place that just suits you as a school-home? That is, perhaps your mothers and fathers are looking anxiously, and know enough about this matter to have discovered that good, safe, Christian school-homes are very hard to find. I thought you might like to know of one which your friend Pansy knows thoroughly, and endorses with all her heart. The ladies in charge she knew years ago; knew them as scholars, when they were formidable to some of us, because they took all the prizes; knew them as graduates of a seminary which was a power in that region, and which was proud of their scholarship.

If you want, any of you, to know more about that home-school, just address a letter to Miss Nanie Toll, New Hartford, Oneida County, New York, and you will be promptly and carefully answered.

Yours in love,

Pansy

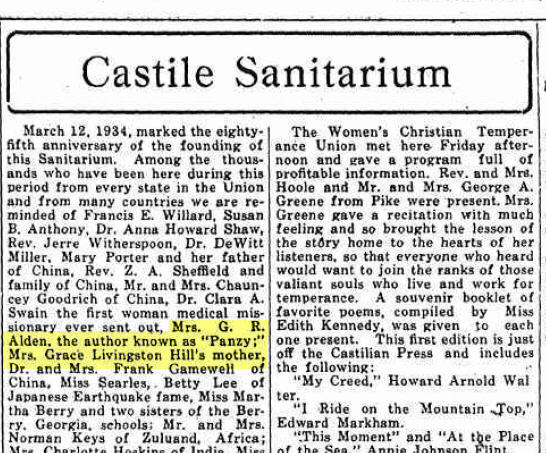

Isabella wrote this sweet article (and glowing recommendation) for an 1876 issue of The Pansy magazine.

Do you like the way Isabella described the school and its surroundings? She was very familiar with the place she described, since she lived in the same small town.

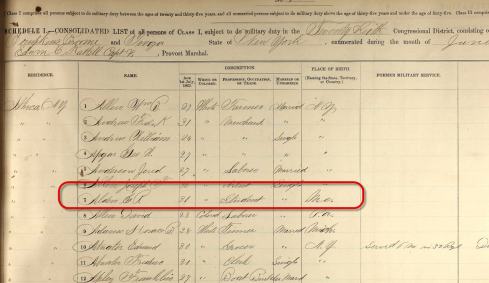

Isabella’s husband was the minister at New Hartford’s Presbyterian church when her best friend Theodosia selected New Hartford, New York as the location for her school.

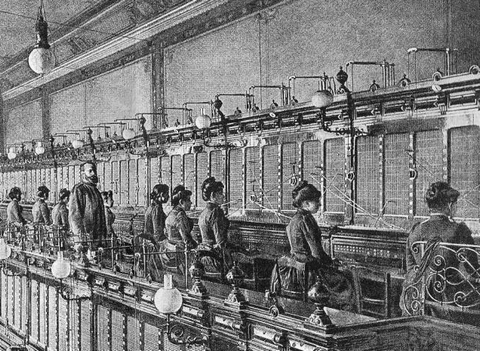

Can you imagine how wonderful it must have been for Isabella and Theodosia to be able to spend so much time together again, just as they had when they were young girls at boarding school?

You can read more about Isabella and Theodosia’s friendship in these blog posts:

Locust Shade … and a New Free Read!

Free Read: The Book that Started it All