Last week Apple unveiled its new iPhone with the latest innovations in communication technology. Its release came 130 years after Isabella Alden first mentioned the telephone in the plot of one of her novels.

As convenient and indispensable as phones have become in our modern age, the same could be said of telephones in Isabella’s time. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, telephones changed the way Americans lived.

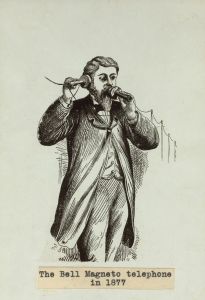

Isabella was 35 years old when Alexander Graham Bell patented his version of the telephone in 1876; but that first model had very limited capabilities.

.

Although the early Bell telephones certainly transmitted sound, they only worked between two locations that were hard-wired to each other.

.

Then, in 1878, a man named George Coy invented the telephone exchange and immediately turned the telephone into a much more practical invention.

Instead of telephone lines being strung between two locations as Bell had envisioned, Coy’s exchanges linked any number of telephones to a single point: a switchboard.

,

At the exchange, legions of trained switchboard operators used a series of cords and sliding keys to connect and reroute incoming calls to other telephones linked to the exchange.

.

Thanks to those exchanges, telephone line construction exploded with growth over the next few years. By 1880, there were 47,900 telephones across America. By 1881, telephone service between Boston and Providence was established. By 1892, a telephone line had been constructed between New York and Chicago; and two years later New York and Boston were connected.

.

Another benefit of those exchanges: jobs. As telephone service expanded, more and more trained switchboard operators were needed to connect calls; and the majority of the operators hired were women.

.

When Isabella published her novel Eighty-Seven, she included a character who worked as a switchboard operator. Her name was Fanny Porter, and she worked in the Dunbar Street Telephone Office. Another character in the story described Fanny as …

… a bright, pretty girl, young, and quite alone here. She lives in a dreary boarding-house, and used to have some of the most desolate evenings which could be imagined.

.

Fortunately, not all switchboard operators lived and worked under such conditions. While the majority of switchboard jobs required working for a Bell Telephone Company, there were other positions available. For example, some large businesses that required multiple telephone extensions were equipped with their own exchanges and hired operators to run them.

In fact, businesses were the foremost users of the telephone in the late 1890s. That’s because, in general, phones were too expensive for individual homeowners to install and maintain; but Mr. Mackenzie, the wealthy businessman in Isabella’s novel Wanted, could afford to have a telephone in his home.

In fact, the telephone plays a small but pivotal role in the story. When Rebecca Meredith, the novel’s heroine, first meets Mr. Mackenzie, she thinks he’s hateful and selfish, until she mentions one evening that his young daughter is a little hoarse. To her surprise, Mr. Mackenzie immediately telephones the doctor and …

… administered with his own hand the medicine ordered. Even after the doctor had made light of fears and gone his way, the father sat with his finger on Lilian’s small wrist and counted the beats skillfully and anxiously.

After witnessing his tenderness for his daughter, Rebecca begins to change her opinion about Mr. Mackenzie.

In her 1892 book, John Remington, Martyr, Aleck Palmer was also a young man of great fortune; he, too, had a telephone in his home and business, which caused Mrs. Remington some concern. You see, she was intent on playing matchmaker between Aleck Palmer and her friend Elsie Chilton and invited the unsuspecting couple to dinner without letting either know the other had been invited. As Mrs. Remington explained to her husband:

Elsie is getting to be such a simpleton that I am afraid she would run home if I should let her know he was coming; and as for him, he is developing such idiotic qualities in connection with her, that I feel by no means certain he would not get up a telephone message or something of the sort to call him immediately to the office, if he should know before the dinner bell rang that Elsie was in the house.

But by the time the 20th Century dawned, the demographics and cost of telephone usage changed dramatically. Telephone companies had connected most major cities and strung sufficient telephone lines across the country to bring costs down, and phone company executives began to set their sights on a new goal: providing service to residential customers.

At first, advertising to consumers stressed the obvious: keep in touch with friends and family.

.

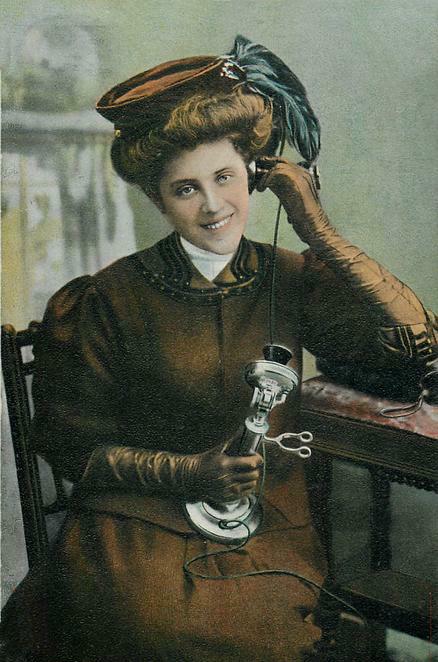

Then, in 1910 the Bell Telephone Companies developed several strong marketing campaigns that offered different reasons why every home should have a telephone. One campaign was directed specifically at the lady of the house.

The ads had strong visual cues, like this one illustrating how a phone in the home meant a family could summon a doctor quickly:

The series of ads was printed in magazines and on postcards, showing how a Bell telephone …

… keeps travelers in touch with home …

… guards the home by night as well as by day …

… summons help during household emergencies …

… relieves anxieties over a loved one …

… and quickly helps arrange replacements when servants fail you.

The ad campaigns were extremely successful. People began to think of telephones as an essential tool for the home, instead of a mere convenience. Soon, telephone companies across the country were installing residential telephones at an astonishing pace.

.

And after each new installation was complete, telephone residential customers notified friends and family of their new phone number by sending out cards like these:

.

Soon telephones became not only an essential device for the home, but a convenient tool for the lady of the house. In Ester Ried’s Namesake, published in 1906, Ester Randall worked as a cook in the home of the Victor family. And being a stylish family, the Victors, of course, had a telephone, which Mrs. Victor used regularly, as in this scene where she explained to Ester her plans for dinner:

We’ll make the dinner light and easy to manage; just a steak and some baked potatoes and canned corn. Did you say there was no corn? Oh, I remember, you told me yesterday, didn’t you? Well, just phone for it. Call up Streator’s, they are always prompt; tell them they must be. And we’ll just have sliced tomatoes with lettuce for salad; all easy things to manage, you see. As for dessert, make it cake and fruit—strawberries, or peaches, it doesn’t matter which. Why, dear me, that dinner will almost get itself, won’t it?

It’s amazing to think that Isabella Alden saw the development of one of the greatest inventions of the Twentieth Century. In her time the telephone was innovative and exciting. It opened new avenues of jobs for women and changed the way people interacted with each other; and Isabella reflected those changes in her novels and stories that we still read and appreciate today.

You can read more about Isabella’s novels mentioned in this post by clicking on the book covers below: