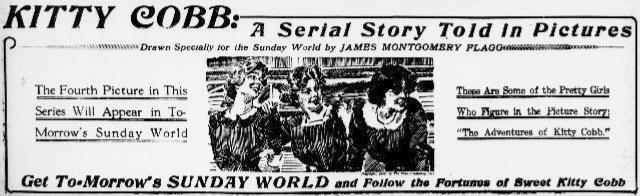

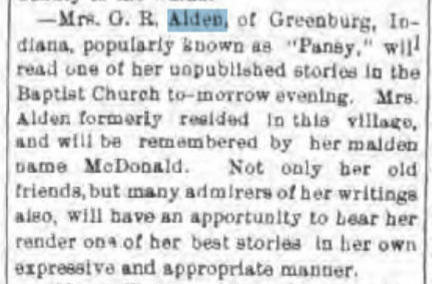

In 1902 Isabella Alden published her most controversial book, Mara.

Mara is the story of a young woman who unknowingly marries a Mormon man with multiple wives. What made Mara controversial wasn’t the plot. Novels with similar themes of an innocent young woman duped into marrying a polygamous Mormon husband had been published for over 50 years.

Author Metta Victor created the sub-genre with her book Mormon Wives, published in 1856. In the book two women, life-long friends, find themselves married to and betrayed by the same Mormon man.

After that book’s success, an estimated fifty novels were published by 1900, vilifying the Mormon religion. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s book, A Study in Scarlet depicted Mormon President Brigham Young as a villain and the Mormon Church steeped in kidnapping, murder and enslavement of its women.

So what made Isabella’s novel Mara different from all the others?

In 1902 when Mara was published, the topic of polygamy was at the forefront of American consciousness. Only a few years before, Americans believed, polygamy had been abolished; they believed plural marriages did not exist because the Mormon Church had assured the Federal Government the practice had been abolished. That assurance had been required of Utah as part of its transition from territory to state.

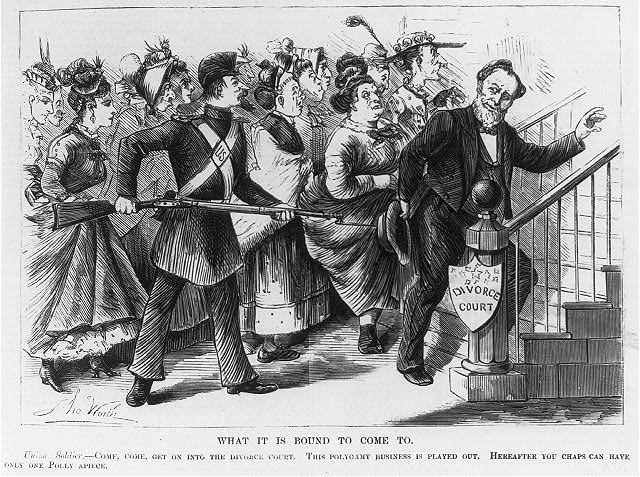

Utah’s transition had been a long and contentious process. The Federal Government had tried numerous ways of outlawing polygamy in the past through the 1862 Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act, and again in the 1882 Edmunds Anti-Polygamy Act. But the LDS Church defied the laws and continued to sanction plural marriage. Under President Grover Cleveland the Federal Government tried to enforce the laws by arresting and imprisoning men who could be proven to be polygamists.

But the Federal Government’s only effective weapon was blocking statehood, and residents of Utah keenly felt the effects. They couldn’t vote in Federal elections and their territory was ruled by a governor, secretary and judges appointed by the President of the United States.

In 1890 the LDS Church appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, arguing the Edmunds Anti-Polygamy Act was unconstitutional because it prohibited Mormons from practicing their religion, of which plural marriage was an essential part. The U. S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Edmunds Act.

In 1890 Mormon Church president Wilford Woodruff published his “Manifesto,” which declared an end to the practice of polygamy in the Church. Doing so paved the way for Utah to become a state; and six years later Utah joined the Union. Protestants in America breathed a sigh of relief.

But almost immediately after the Manifesto was issued, certain members of the Mormon Church resumed the practice of polygamy clandestinely. Ranking members of the Church’s Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and other members of the Church entered into plural marriages—and sanctified plural marriages of others—in direct defiance of the Manifesto.

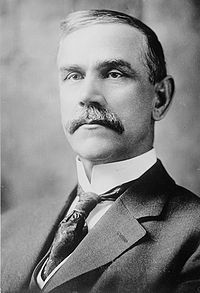

The rest of the country felt it had been duped and a wave of outrage swept across America. Some believed there was a great Mormon conspiracy to take over the U.S. government. Concern deepened when the Utah Legislature chose Reed Smoot—a member of the Church’s Quorum of the Twelve Apostles—to be the State’s new Senator.

Protestant churches organized massive petitions against allowing Mr. Smoot a seat in the Senate; and the U.S. Senate responded by conducting a multi-year investigation into the Mormon Church and its influence in the state of Utah.

Mara was written in the climate of that time. Like other anti-polygamy novels before, Mara’s plot centered around a young woman who married a successful and gentlemanly man from Utah, only to later discover she was his latest in a string of wives. Mara was also a reminder to readers that America had to remain vigilant in ensuring polygamy as a practice was removed from American society.

Today some might think Mara’s plot is simply sensational fiction; but Isabella Alden’s novels were always rooted in a common truth: her characters lose their way only when their relationship with God wanes. She used the story to show how easy it was for a young woman to fall under a wrong influence in a time of weakness in her life.

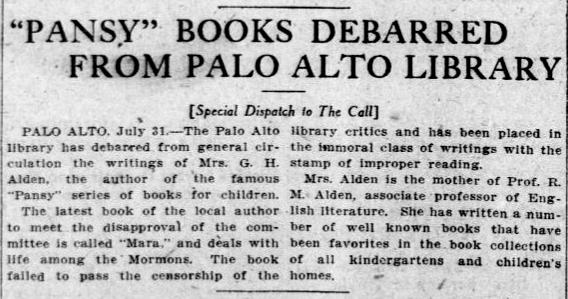

In Mara Isabella also displayed some sympathy for the wives and children of the plural unions, which may have been one reason the book came under scrutiny. Some public libraries, including the library in Isabella’s town of Palo Alto, California, banned the book because it dealt with the topic of polygamy, which library trustees considered an immoral practice.

America, for the most part, did not share Isabella’s pity. Their abhorrence for polygamy (and all who engaged in the practice, including the wives) reached new heights during the four years it took the U.S. Senate to conduct their investigation into practices of the Mormon Church. In the end, the Mormon Church submitted to pressure and outlawed polygamy once and for all, and established a new practice of excommunicating Church members who entered into plural marriages.

Reed Smoot was eventually seated as a United States Senator from the State of Utah. He served his state and his country honorably for almost thirty years, and, by his conduct, helped force a profound shift in America’s perception of Mormonism.

Eventually, Mara was returned to the shelves of the Palo Alto Public Library, but many libraries and stores considered the book too controversial to stock.

Discover more about the events in this post:

Read about Utah’s Road to Statehood

Read more about Pansy’s Banned Books

The U.S. Senate’s page about The Expulsion Case of Reed Smoot of Utah

Watch a video about Mormon President Joseph F. Smith’s testimony before the U.S. Senate

Read the testimonies of Mormon President Joseph F. Smith and Reed Smoot before the U.S. Senate

Read Mara for free.

Click on the book cover to read an unabridged edition of the book.

Click on the book cover to read an unabridged edition of the book.

.

.