Between 1900 and 1910 American consumers were introduced to some revolutionary new inventions and products that would significantly change their lives. In 1903 the Wright Brothers powered their first sustained airplane flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina.

In 1908 the first Model T Ford automobile rolled off the production line in Detroit, Michigan.

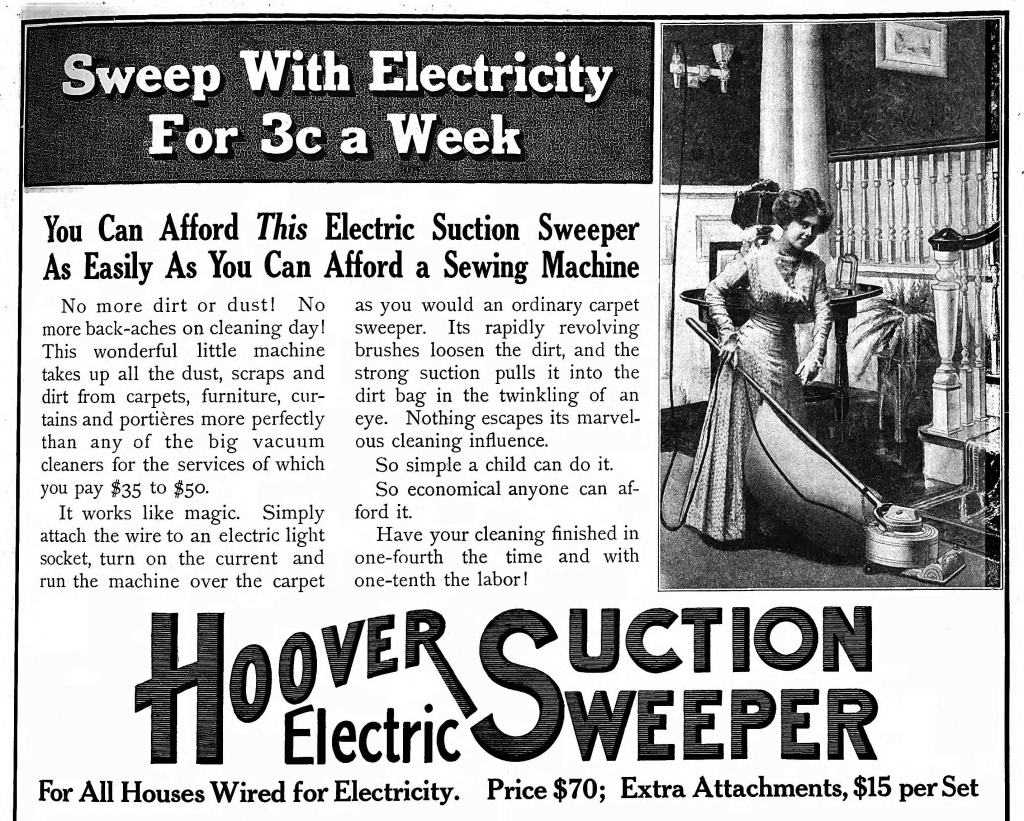

Other inventions during the decade included the safety razor (1901), Cornflakes (1907), teabags (1904), washing machines (1908), and vacuum cleaners (1901).

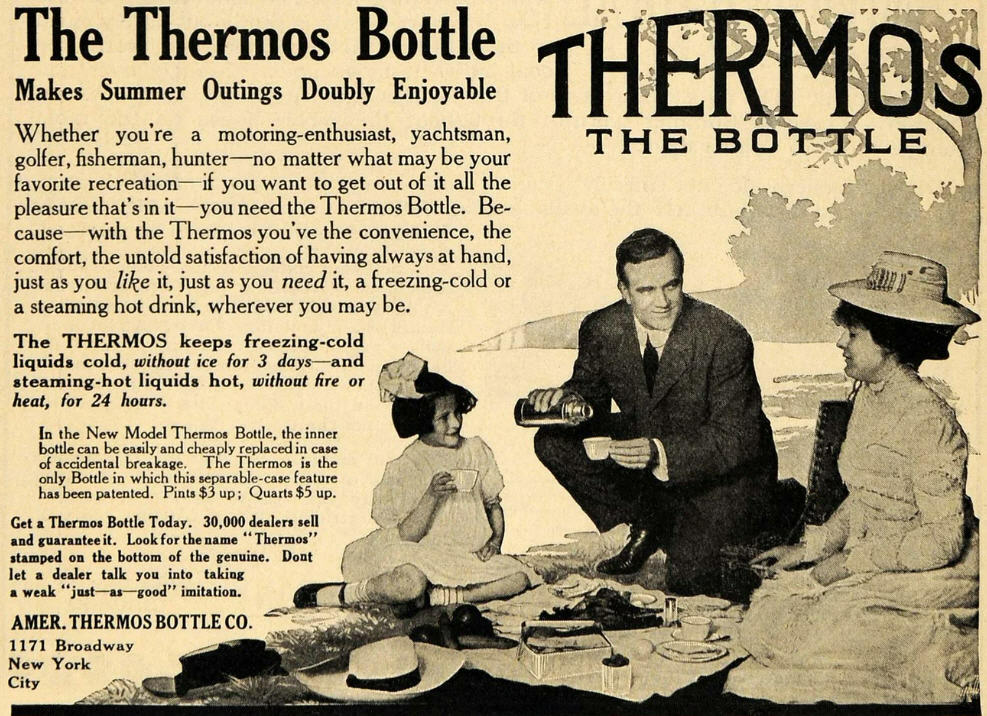

But in 1907, an entirely new product took the country by storm: the Thermos bottle. This cleverly designed vacuum bottle could keep drinks hot or cold for hours—something no other portable container could do.

It’s easy to imagine Isabella Alden embracing this new invention, especially given the lifestyle she adopted after she and her family moved to California around 1901.

The Aldens settled in Palo Alto, where son Raymond was teaching at Stanford University. A few years later, Isabella and her husband became involved with the newly-founded Mount Hermon Christian camp near Santa Cruz. Mount Hermon reminded her of her beloved Chautauqua Institution, and it quickly became her summertime place of peace where she could rest, read, and worship among the giant redwood trees. Isabella recalled:

“Tent life seemed to belong to it as much as houses belong in most other places. We ate out of doors, and worked out of doors, and practically slept out of doors, with all the curtains of the tent looped high.”

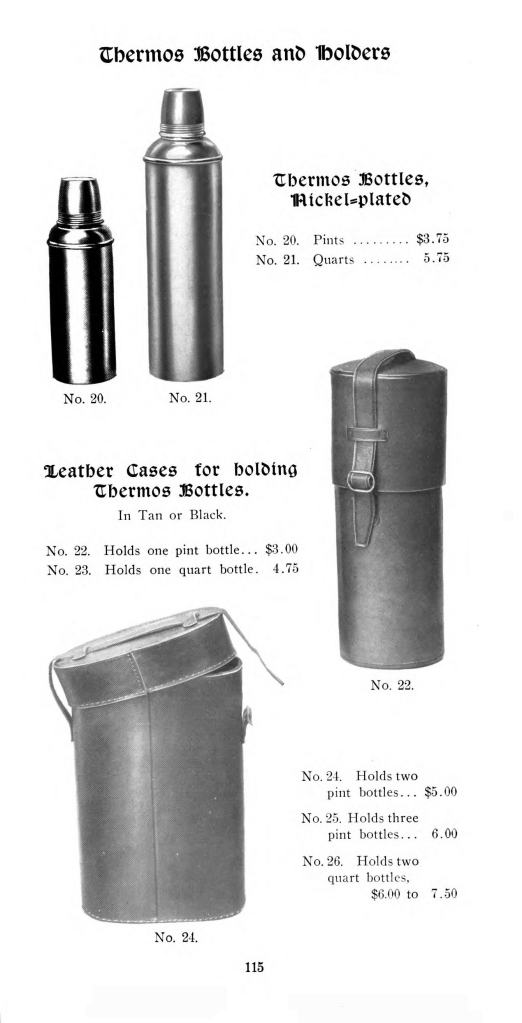

When Thermos bottles first appeared in stores, they were luxury items. Depending on size, prices ranged from $3.50 to just over $5.00—the equivalent of about $125 to $150 in today’s money.

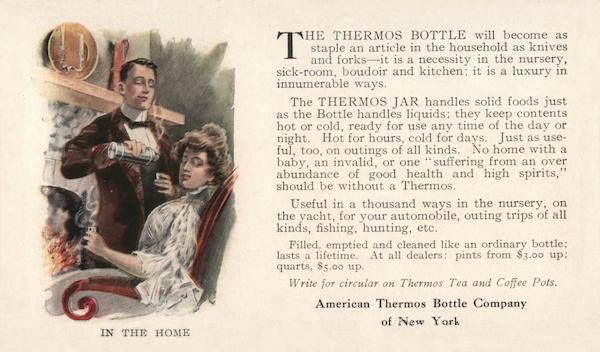

Travelers quickly embraced the Thermos bottle as a necessity worth the investment. Upper-middle class households purchased them, too, using Thermos bottles to keep food and drinks at stable temperatures without relying on wood-fire stoves, electricity, or refrigeration—all expensive options.

The American Thermos Bottle Company of Norwich, Connecticut, launched a full ad campaign in magazines, trade journals, and newspapers. As sales increased, they launched additional products—pitchers and carafes, food storage bowls, and even completely furnished picnic baskets. With growing demand came increased production, and by the 1920s Thermos bottles were much more affordably priced.

Isabella never specifically mentioned a Thermos in her memoirs or her stories, but throughout her life she eagerly embraced new inventions and technologies. It seems probable that during those early rustic summer days at Mount Hermon, she might have had a Thermos bottle at her side for a cool drink of water.

Isabella’s niece, author Grace Livingston Hill, was also quick to embrace new inventions, and mentioned Thermos bottles in her novels, including The Prodigal Girl (1929) and The Street of the City (1942). In her novel Ladybird (1930), Grace wrote about the main character Fraley MacPherson marveling over a picnic lunch:

“There were other little packages with other sandwiches, some with fragrant slices of pink ham between them. There were hard-boiled eggs rolled in paper. There were olives and pickles, and chocolate cake and cookies, and white grapes and oranges—a feast for a king! There was coffee amazingly hot in a Thermos bottle. And in the wilderness!”

Whether or not Isabella actually owned a Thermos, she certainly lived during one of the most innovative decades in American history—and she took advantage of it. Her writing shows someone who was genuinely curious about new inventions and quick to see how they might improve her daily life. That openness to change and progress is just one more reason her work still feels surprisingly modern today.

You can read more about how Isabella embraced new inventions and technology in these posts:

New Free Read: “Midnight Callers”

A New Luxury

iPhones and Isabella

It’s National Sewing Machine Day

The Edison Connection

“She’s a Beauty”