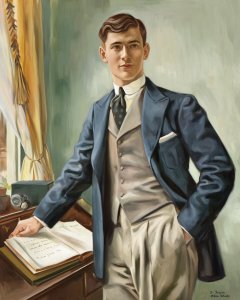

Isabella often drew on her own life experiences when writing her stories and novels.

For example, Isabella’s husband G. R. “Ross” Alden was a seminary student when he and Isabella were courting. On the very day of their wedding, Isabella and Ross boarded a train to take them to a new town where Ross was assigned his first church as a minister. Isabella used the very same circumstance in her 1890 novel Aunt Hannah and Martha and John. In the story, newly married Martha also left her parents’ home immediately after her wedding to go with her new minister husband to his first church.

And just as Isabella had to learn the best she could to be a good minister’s wife, Martha had to do the same in the novel. One scene in the book tells what happens when Martha attends a ladies’ prayer meeting soon after she and John arrive at the new church. Here’s how Martha described the meeting to John later that day:

It wasn’t pleasant, John. It was, well, dreadfully stiff; I don’t know any other word that will describe it. Almost everyone was late, yet the meeting did not begin; they sat around solemnly and looked at one another. At last someone ventured to ask Mrs. Jones to lead. She said that she was not prepared, and that she didn’t feel competent to lead a meeting, anyway. Of course that made all the others feel as though they ought not to be ‘competent,’ and one and another refused. Then our next neighbor said she thought the minister’s wife was the proper person to lead; but by that time I was so sort of frightened that it seemed to me I couldn’t lead anything, and I said I did not feel competent, either.

Mrs. Green was finally persuaded to lead; she selected a long hymn and read the whole of it. Think of reading a hymn, John, in a little informal prayer-meeting that is to last only an hour! Then they had a time getting someone to start the tune. Mrs. Jones said she was hoarse, and Mrs. Brown did not know any tune that would go with the words. At last I grew ashamed of myself, and started a tune that I thought everybody in the world knew, but hardly anyone sang, and that frightened me. But they all looked as solemn as though they were at a funeral.”

Poor Martha! She felt she disgraced herself as the new minister’s wife. If only she had been trained in how to lead a prayer meeting!

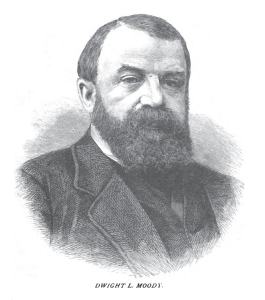

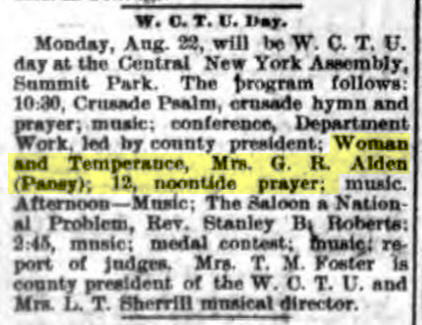

In her real life, Isabella had to learn the same lesson. Fortunately for her, she had expert advice from a close friend of the Alden family: Reverend Dwight Lyman Moody.

Rev. Moody was a world-renowned minister and evangelist. In 1897 he wrote this bit of advice about prayer meetings, which Isabella published in a Christian magazine she edited:

Several important matters must be considered in order to have a good, live prayer meeting. Of course, the all-important thing is the presence of the Spirit of God, without whom no spiritual blessing can come. But there are certain things on the human side that help or hinder success.

First of all, the physical conditions. I do not believe even the angel Gabriel could infuse life into a meeting that is held in a dull, close room. Let there be plenty of fresh air. Make the room bright and cheerful, and there will be little chance of people’s falling asleep.

The meeting should begin and end promptly on time. Announcement should be made on Sunday, and a cordial invitation given to everybody to attend. If the prayer meeting is held in contempt, it is useless to expect a blessing there. I know some churches where they look forward to it more (if anything) than to the Sabbath services.

It is a good plan to allow about a quarter of an hour at the beginning for singing, another quarter for the leader to read Scripture and introduce the subject of the evening, another quarter for prayer and testimony, and the remainder of the hour for special prayer. But I do not suggest this as a permanent division of the time. Avoid falling into ruts of any kind. If some leading minister can attend, let him occupy the whole time; and introduce variety in other ways.

The music should not be neglected. Paul says, “In everything, by prayer and supplication with thanksgiving, let your requests be made known unto God.” I take it that thanksgiving and praise can best find expression in songs in which all can join. It is therefore important to have an active, earnest leader of the singing, who is able to read the pulse of the meeting, and by striking up suitable and familiar hymns, bridge over a pause, if need be.

A GOOD LEADER.

The success of the meeting depends largely on the leader. If he is full of life and of the Spirit, the audience will catch his enthusiasm: but a cold, listless manner throws a wet blanket over the proceedings.

He should be there ten minutes before the meeting begins, in order to see that everything is in good order, and he should come prepared to lead. If there is one thing that will kill a meeting sooner than another, it is to have the leader stand up and state that he has not come prepared. If a subject has been announced, it is his duty to study it so that he can introduce it intelligently. If he is not limited to any special subject, let him introduce one that appeals to the hearts of the people, and that they can speak upon without special preparation. When I was in charge of a work in Chicago, I used to say, “I am going to take up the Good Shepherd (or some such topic) tonight,” and then got friends to quote texts or make remarks on that subject. Let the leader set an example by being short and to the point in his opening remarks.

As at all other services, I believe the best thing to do is to feed the people with Scripture. Why is it we have so much backsliding, so little growth in grace? Because of the lack of food for the soul. If one neglects the Bible, his soul becomes starved and easily stumbles. “As newborn babes desire the sincere milk of the Word, that ye may grow thereby.” The more men love the Scriptures, the firmer will be their faith. And if they feed on the Word, it will be easy for them to speak; for out of the abundance of the heart he mouth speaketh.

Like everything else, the plan of announcing a topic beforehand can be abused. The objection is raised that in many meetings they go together, have one or two prayers, and discuss a topic. There is no need to pervert the meeting in this way. Let there be full liberty to all to tell their joys and sorrows, and give their testimony along any line.

A GOOD FOLLOWING.

The success of the meeting must also depend largely on the audience. The leader is not a Goliath, to go forth alone. Of all church services, the prayer meeting is the one specially intended for church-members to take part in, and the subject should be such as to draw them out. The leader should try to bring in fresh voices, even if he has to hunt them up beforehand.

The members should come to the meeting in the spirit of prayer. It ought to be on their hearts from week to week, so that they are thinking about it and praying about it. If a spirit of unity prevails, such as we read of in the case of those early Christians who “all continued with one accord in prayer and supplication,” blessing will surely follow.

I have no sympathy with the excuse that people have not time to attend. Of course there are certain ones whose circumstances or duties keep them away; but with many the excuse is due to sheer carelessness or indifference. Daniel was a busy man. He was set over the princes of a hundred and twenty provinces. Yet he found time to retire to his chamber three times a day to pray and give thanks before his God.

When the meeting is thrown open, friends should be brief and pointed in their remarks. Bible prayers are nearly all short. Christ’s prayers in public were short. When he was alone with God, it was a different thing, and he could spend whole nights in communion. Solomon’s prayer at the dedication of the temple is one of the longest recorded, and yet it takes only six or eight minutes in delivery.

“Lord, help me.”

“Lord, remember me when thou comest into thy kingdom.”

“Lord, save us.”

Such are the prayers that never failed to bring an answer. The prayer that our Saviour left his disciples is a model in its brevity, its recognition of God and desire for the glory of his kingdom, its sense of dependence upon him for daily needs and for deliverance from the guilt and power of sin.

BE DEFINITE.

Beware of vagueness. It is a sure sign that the prayer is heartless and formal. Beware of praying about everything that can possibly be touched upon. Leave something for those who follow to pray about. Beware of falling into ruts. Dr. Talmage says that if we were progressing in our Christian life, old prayers would be as inappropriate for us as the hats and shoes and clothes of ten years ago. Mr. Spurgeon said that some men’s prayers are like a restaurant bill of fare—ditto, ditto, ditto.

I believe in definite prayer. Abraham prayed for Sodom. Moses interceded for the children of Israel. How often our prayers go all around the world, without real, definite asking for anything! And often, when we do ask, we don’t expect anything. Many people would be surprised if God did answer their prayers.

As it is the members’ prayer meeting, special prayer should be offered on behalf of the church in all its varied activities, the pastor and all in authority. Other subjects for special prayer are the sick and sorrowing, the unconverted, and the services of the coming Sabbath.

Before the meeting is closed, an opportunity might be given for the unconverted (if there are any present) to make a confession or rise for prayer. I have one church in mind where they have conversations right along at the prayer meeting. Some testimony, some personal experience of God’s grace and blessing, will often convince a man where sermon and argument fail.

The greatest need of the church today is more of the presence and power of the Spirit of God. O that Christians were roused to greater earnestness and importunity in prayer! I believe that the greatest revival the church has ever seen would result. God help us, each one, to be faithful in doing our share.