For many people, January is a time of new beginnings, a chance to throw off old habits and create new routines that we hope will make us happier, healthier, and more successful.

One resolution that never goes out of style: getting our finances in order. We promise ourselves we’ll spend less, save more, or stick to a budget. It’s advice we hear everywhere, from financial gurus to social media influencers.

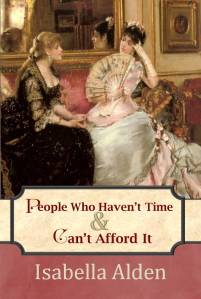

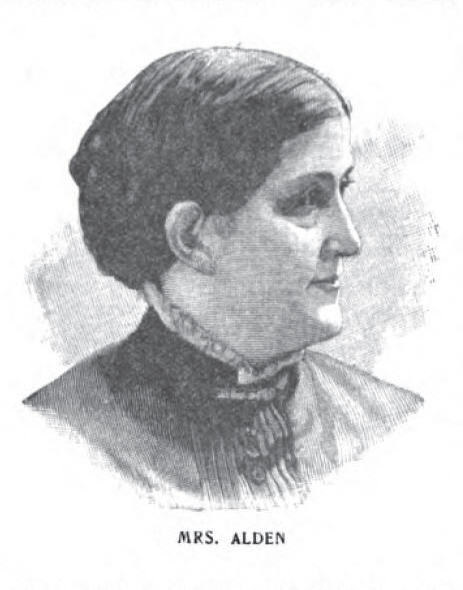

But more than a century ago, Isabella Alden was already writing about these same challenges, and offered practical wisdom about money management that remains true today.

Isabella was well acquainted with the concept of living within your means. Growing up, she watched her parents practice small, daily economies. They instilled in Isabella a belief that buying anything on credit—from running a tab at the green grocer’s to carrying a mortgage on a home—could lead to financial ruin.

When she was twenty-five, Isabella married a newly-ordained minister and kept house with very little income. It wasn’t until she began writing her books and stories that she started to earn money to augment her husband’s meager salary.

Money (and the lack of it) was a frequent theme in Isabella’s books. In Aunt Hannah and Martha and John Isabella wrote about the trials of a young minister’s wife who has to learn to cook and clean in order to economize (often with comical and disastrous results). Some of the scenes in the novel are based on Isabella’s own experiences.

So it isn’t surprising that she would be wise about money, and would believe wholeheartedly in the concept of living within one’s means.

Here’s an essay she wrote on the topic for an issue of The Pansy magazine in 1878:

GRAIN BY GRAIN

Did you ever know a young man, when he began in earnest to work for a living, who ever had wages enough? Somehow, salaries and “wants” never do keep with each other. There are not many, who, like an old philosopher, can walk along the streets of a gay city and note the tempting wares set out on every side, and yet say, “How many things there are here that I do not want!” Yet if you can get a little into his way of looking at the luxuries of life, it will be a great help to your peace of mind.

And it is a very singular fact that most fortunes have been laid on very small foundations. A great merchant was accustomed to tell his many clerks that he laid the foundation of his property when he used to chop wood at twenty-five cents a cord. Whenever he was tempted to squander a quarter he would say, “There goes a cord of wood!” He learned in very early years a good lesson in practical economy.

An old woman had been seen for years hanging about the wharves, where vessels were loaded and unloaded in New York harbor, intent on picking up the grains of coffee, corn, rice, etc., that were by chance scattered on the piers. The other day she was badly hurt by some heavy bags of grain falling on her. The kind merchants took up a purse for old Rosa and sent her to her home in Hoboken, in charge of an officer. What was his surprise to find that the neat and handsomely furnished cottage was the property of the old grain picker? She had literally built and furnished it, as the coral workers do their homes, grain by grain.

Do not be discouraged though your profits are small. If you cannot increase the income, the only way out of the difficulty is to cut down the wants. Turn every claim to the best account, and as prices go, you will be able to get a vast amount of real comfort out of even a small income. The habits you are forming are also of the greatest importance, and may be made the foundation stones of a high prosperity.

Have you ever had a “grain by grain” moment—where small consistent choices added up to something significant over time?

If you had to choose just one principle from Isabella’s essay to focus on this year—cutting unnecessary wants, maximizing what you have, or building better financial habits—which would make the biggest difference in your life?

![A square label affixed to the inside cover of a book. On the first line of the word "NO" with room to write a number; the number 61 was written and crossed out, and the number 77 written beside it. Below are printed "SUNDAY SCHOOL LIBRARY of the Evengelical [sic] Lutheran Church, Springfield, Ill." The text is surrounded by a fancy Victorian-era design of swirls and dots.](https://isabellaalden.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/evangelical-lutheran-church-book-plate.jpg?w=1024)

![Newspaper clipping: The committee in charge of the arrangements make this further announcement: “We desire again to call the attention of all parents, Sunday School workers, and especially all young people, to this unlooked for opportunity to meet and greet Mrs. G. R. Allen [sic], “Pansy.” She is known and loved as the author of such helpful and thrillingly interesting books as “Ester Ried,” “Four Girls at Chautauqua,” “The Hall in the Grove,” “One Commonplace Day,” etc. Her engagement with the State Sunday School Assembly at Ottawa, Kansas, brings her west at this time and we trust that a “crowded house” will show our appreciation of the extra effort she is making to come to Wellington. The other speakers from abroad, and those among us who have kindly agreed to assist in these meetings, will give us a feast of good things. Come everybody and enjoy the feast.](https://isabellaalden.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/06-11-05.jpg?w=544)