It’s Christmas time, and shopping for the holiday is now in full swing. During Isabella’s lifetime, Christmas ads filled the issues of newspapers and magazines, tempting shoppers with bargains and gift ideas.

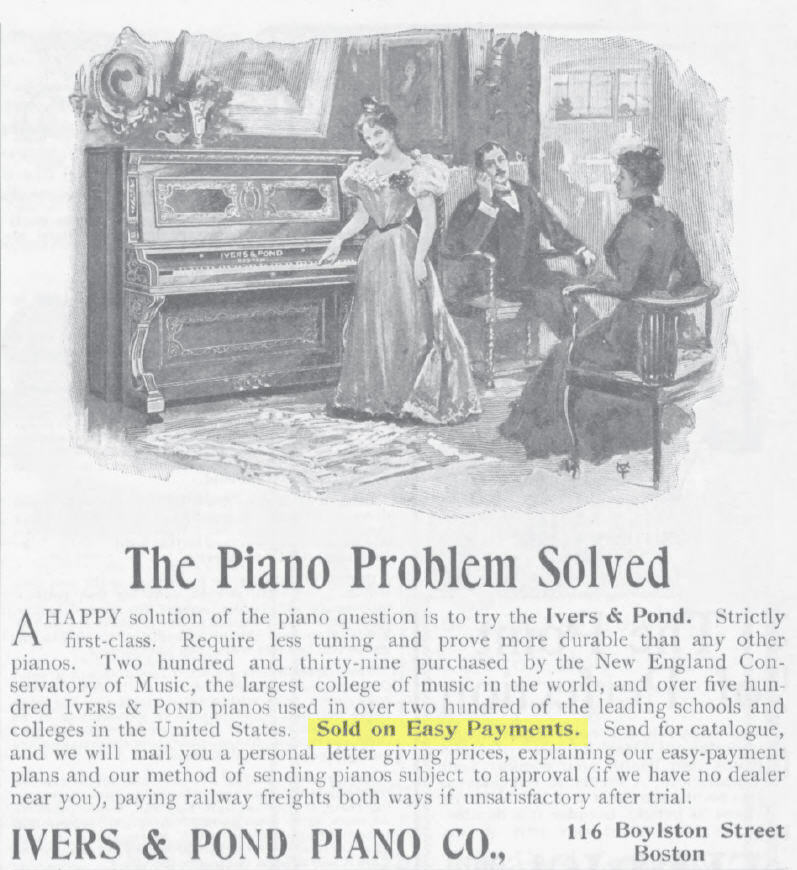

Among the many advertisements for books, handkerchiefs, slippers, and gloves were ads for a gift the whole family could enjoy: a piano.

The idea wasn’t as extravagant as it might sound; by the late 1890s pianos were quite affordable. Dealers and manufacturers offered consumers credit or payment plans that made purchasing a piano within the reach of families with more modest incomes.

Families weren’t the only ones who took advantage of these arrangements. In Pansy’s Advice to Readers, Isabella wrote about a group of school girls who bought a piano for their gymnasium by raising the money themselves and making regular payments to the dealer.

Such arrangements meant pianos were no longer an article of luxury available only to the wealthy. As more families were able to purchase pianos, American social life began to change. Previously, people gathered at churches, concert halls, and other public places to enjoy music; but affordable pianos allowed people to enjoy music at home and within their own family circle.

But even affordable pianos presented a challenge: someone had to learn how to play them.

Once a piano was installed in a home, there were lessons to be had and endless hours of practice in order for a player to become proficient. But in the 1890s self-playing devices came on the market that again changed how families brought music into their homes.

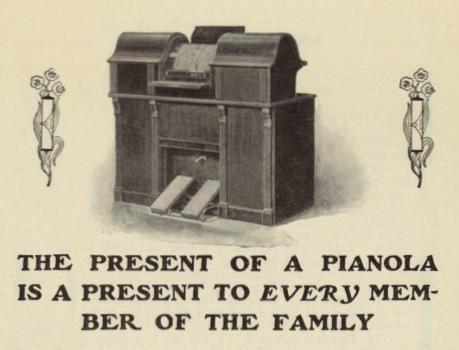

There were two kinds of self-playing devices: those that attached to pianos, and those that were placed inside them.

Invented in America, the pianola was a cabinet-type device that was pushed up against a piano keyboard. It depressed the piano keys with protruding felt-covered levers controlled by a perforated paper roll. A person had to be seated at the device to work the pumping pedals so air pressure created suction to rotate the roll.

The other type—the player-piano—operated in the same manner with a rotating perforated roll, but the device was installed within the piano itself.

According to the editor of The Piano and Organ Purchaser’s Guide for 1908, these devices “made tens of thousands of pianos eloquent with good and popular music”—pianos that formerly were silent, except when there was a dance at home, or on a Sunday, when a few hymns were played.

“The present of a pianola is a present to every member of the family.” So declared a magazine advertisement in 1904 that urged consumers to consider buying a mechanical piano player for Christmas.

It wasn’t just families that could now listen to beautiful music in their homes. This ad in a 1904 issue of Booklover’s Magazine suggested a pianola cabinet player was the ideal gift for a bachelor’s home.

Those self-playing piano devices opened up whole new musical worlds for people. Many who never visited the opera or a concert before became thoroughly acquainted with world-class musical and orchestral compositions.

Sales of pianolas and player pianos peaked in the mid-1920s when gramophone recordings and the arrival of radio caused their popularity to wane.

But while in their heyday, pianos, pianolas, and player pianos made an important mark on American culture, bringing music and joy to thousands of families. Isn’t that a wonderful gift to receive?

You can learn more about pianolas and player pianos by clicking here.

You can read Pansy’s Advice to Readers for free!

Choose the reading option you like best:

You can read the e-book on your computer, phone, tablet, Kindle, or other electronic device. Just click here to download your preferred format from BookFunnel.com.

Or you can select BookFunnel’s “My Computer” option to receive an email with a version you can read, print, and share with friends