Isabella often wrote stories that featured children trying to earn money to help support themselves or their families.

Long before today’s labor laws and social service programs existed, children worked long hours in factories or in the homes of wealthy people, usually for pitiful wages.

Eleanor H. Porter, the famous creator of the Pollyanna books, wrote about the plight of one such child in her novel Cross Currents.

And famed artist Thomas Benjamin Kennington painted a series of portraits of homeless and destitute children in an effort to raise awareness of the problem.

Isabella’s novels The Man of the House, Miss Dee Dunmore Bryant and Twenty Minutes Late all dealt with the issue of children’s working conditions in cities across America; but Isabella always made certain her books had a happy ending. She imbued her young characters with high ideals and strong work ethics that often brought them to the notice of a wealthy benefactor who changed their lives.

That was the case in Isabella’s short story, “Which Way?” about a twelve-year-old boy trying to make enough money to pay the rent on his family’s home. It first appeared in The Pansy magazine in 1889 and you can read it here:

Which Way?

He was a curly-headed, pleasant-faced boy, of about twelve; his clothes were growing short at the ankles and wrists, and were a good deal patched, yet there was a neat trim look about them that one liked to see.

He stood at the corner where two roads met, balancing in his mind the important question which way to go. Both roads led homeward, by an almost equally direct route; one was a trifle sandy part of the way, the other was up hill.

“Hill or sand?” he said to himself, with a smile. “It makes a lot of difference in a fellow’s lifetime which! What if it did, though? What if it should make a difference all the rest of my life? He told about smaller things than that bringing great things out of them. If I had a penny I might toss it up, only I don’t believe he thinks that’s the way to decide things.

“He” meant a stranger whose satchel the boy had carried that afternoon, and who, as they walked along, had spoken a half-dozen cheery words to him about the importance of little things; helping the boy to think more gravely, perhaps, than he ever had before. Then the stranger had gone his way on the three o’clock train, and Jamie never expected to see him again; but he could not help thinking a little about the words. To tell the truth, but for these words to think about he would have been very downhearted.

It was toward the close of a long summer day, in which he had been tramping from one end of the town to the other in search of work, and had failed. It was the old story, father dead, mother hard-worked and poor, with two children younger than Jamie to care for. There was great need that he should find work to do. The dreadful rent, which seemed to eat up every penny, was nearly due again, and little Eddie had been sick for a week, hindering his mother from going out to her regular day’s work, so that times were harder than ever before.

On Monday morning Jamie had started out with a brave heart, sure that for a strong and willing boy of twelve, there must be plenty of work to do; but now it was Thursday evening, and though he had tramped faithfully from morning till night, no steady work could be found, only a few odd jobs; which, though his mother told him would help a great I deal, seemed very small compared with what he had meant to do. It seemed hard to have to go home and say that he had failed again. This was why he loitered by the way, and tried to fill his mind with other things.

“I’ll go this way,” he said at last, dashing down the less familiar street. “Who knows what may happen?”

What “happened” was that the hostler at the great stone house on the corner, who had been kind to Jamie, called to him as he passed to ask if he would take a note to his cousin Mary Ann who lived at Mr. Stewart’s on the next corner.

Of course Jamie was glad to accommodate him and made all speed to the great house of whose gardens he had often wished he could get a closer view. A game of tennis was in progress here. Jamie stood a moment watching the graceful movements of the players; wondering, meantime, which way to turn to find Mary Ann. Presently the lady who seemed to be the chief one of the group noticed him, and he made known his errand.

“Mary Ann? Oh, yes, she is in the laundry, I think; or no, she is probably upstairs by this time. Wait a moment, my boy, and I will see if I can find her,” and she took her turn in the game.

“Are you in haste?” she asked presently, turning to him with the pleasantest smile Jamie thought he had ever seen in his life.

“Oh, no, ma’am,” he said, returning the smile, “I’m never in a hurry.” His face sobered instantly as the fact that he had no work to make him feel in haste, came back to him unpleasantly. It appeared that the game was very near its close; a few more turns, and with much laughter and many pleasant words the players said good-night, leaving the young lady and Jamie alone. He was glad that her side had beaten.

She turned toward him, smiling. “So you are never in a hurry; that must be a rather pleasant state of things.”

“I don’t know, ma’am,” said Jamie again. “I guess I’d like to have a chance to be in a hurry.”

“Would!” with lifted eyebrows and an amused, questioning look. “That is strange! I’m in a hurry a great deal of the time, and I don’t enjoy it always. There is Mary Ann at this moment.” She signaled the red-faced Irish girl to approach, and Jamie delivered his note, then turned to go, having made a respectful bow to the lady. But apparently she was not through with him.

“Why do you go away so soon, if you are never in a hurry?” she said pleasantly.

“Why, I’ve done my errand,” said Jamie, “and I supposed the next thing was to go.”

“Why shouldn’t the ‘next thing’ be to come and look at my roses? Bright red and yellow ones. You like them, don’t you? In the meantime you can tell me how you manage it so as not to be in a hurry.”

Jamie followed her with great satisfaction, but finding she waited for his answer, said:

“Why, you see, ma’am, the way of it is, I’ve got nothing to hurry about, and I wish I had. I’ve been hunting for work for three days as steadily as I could, and haven’t found any yet, and am not likely to. That was what I meant.”

“Oh! I understand in part, but I should think your lessons would give you almost enough to do without a great deal of work.”

“I’m not in school, ma’am,” said Jamie, speaking low. “There are reasons why I can’t go very well; mother needs me to help earn the living, so I’m looking for a chance.”

“I begin to understand quite well. What sort of work do you want?”

“Any sort under the sun that I could do; and I could learn to do anything that other boys do if I had a chance,” he said eagerly.

“Such as weeding in a garden, for instance, and picking strawberries and peas? How long do you think it would take you to learn such work?”

“I was born on a farm, ma’am; mother only moved here this spring. It’s just the kind of work I’ve been looking for, but I can’t find any.”

“That is simply because you didn’t come to the right place. My mother has been looking for you all day. I dare say at this moment she is wishing you would come and pick some strawberries for tea, and I’m sure I do, for if you don’t I’m much afraid I shall have to do it myself. I think we would do well to go at once and talk to her about it.”

Jamie, as he followed her up the steps of the broad piazza, his heart beating fast with hope, told himself that he had never seen a sweeter lady in all his life.

Afterwards, while they were picking the strawberries—for she went with him to “show him how,” she said with a merry smile—he told her how he came to take the road home which led past her door; and then, in answer to her questions, how he was led into that train of thought by the earnest words which the strange young man said to him that morning.

“So you carried my brother Harvey’s satchel, did you?” she said, with a bright look on her face. “Very well; one of the ‘little things’ he told about has happened to you. Now you are sure of plenty of work about this house as long as you want it, provided you are a faithful, honest boy, as I seem to know you will be. I think I must have been looking for you; but I’ll tell you what I think, my boy; I don’t believe it is a happen at all. I believe your Father sent you.”

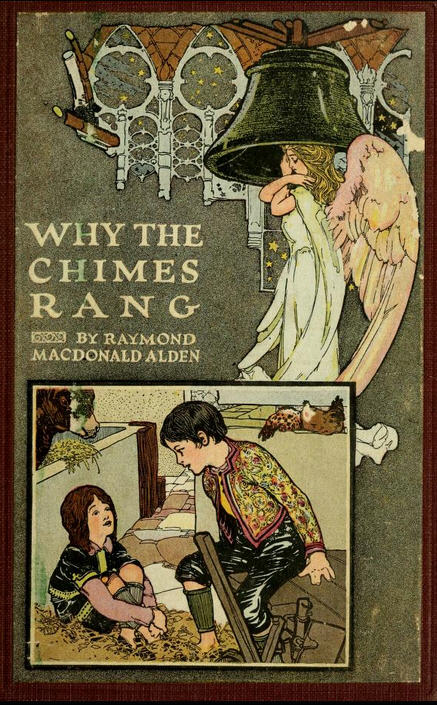

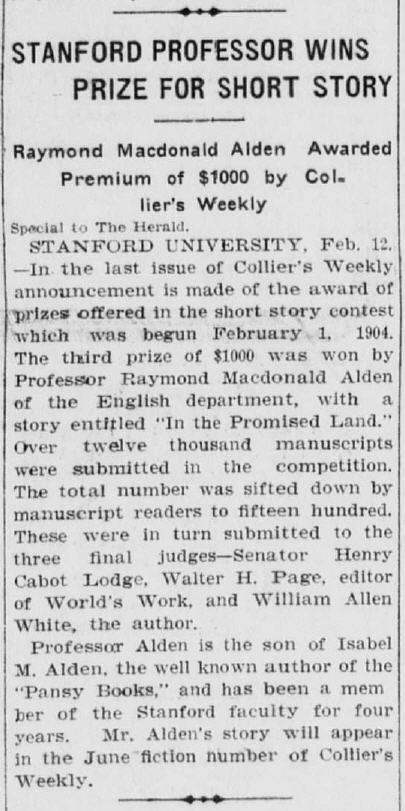

You can click on the cover images to find out more about the books mentioned in this post.