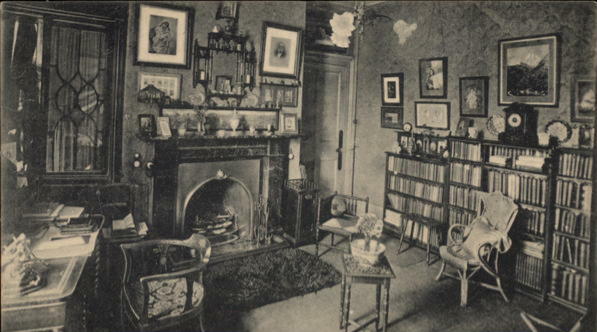

Though we often think of her as a writer of Christian fiction, Isabella Alden had another demanding career: she was an acknowledged expert in developing Sunday-school lessons for children. In her years growing up in a Christian home and, later, as a minister’s wife, she had plenty of opportunities to judge the effectiveness of Sunday-school programs.

She knew that many Sunday-school teachers had no training at all.

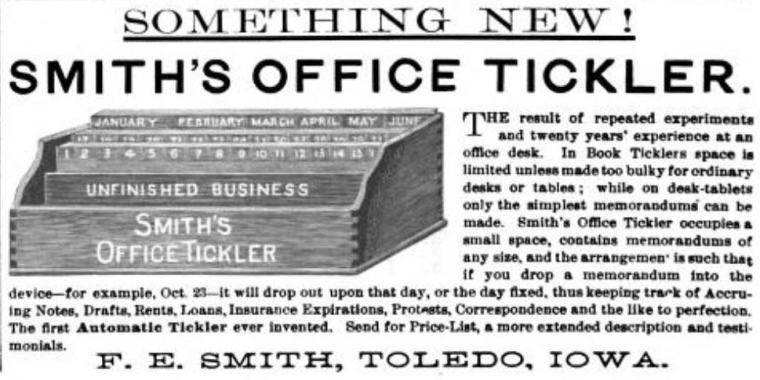

She had seen teachers who didn’t know what the Sunday-school lesson was until Sunday morning when they sat down in front of their class to teach.

She had also seen teachers who didn’t even know the Bible verse on which the Sunday lesson was based.

Isabella knew there was a better way to teach young children the lessons of the Bible in a way they could understand; so she developed a program of education for Sunday-school teachers of young children, in which she gave teachers step-by-step instructions, telling them everything they needed to know … from what to write on the chalkboard, to when to have the children stand and sit.

She shared her program at the Chautauqua summer assemblies, and she spoke at churches about the method. Her Sunday-school lessons were published in regular weekly columns in Christian magazines, such as The Sabbath School Monthly and The National Sunday-School Teacher.

Click on this link to see an excerpt from an 1877 issue of Sabbath School Monthly with one of Pansy’s lessons.

Isabella was convinced that children should be shown that the Bible had meaning for them. She believed children were not too young to learn that the Bible could be a help to them in their day-to-day lives.

It was that premise that inspired her to write three of her most popular children’s books. In Frank Hudson’s Hedge Fence, Frank (a boy of about ten or twelve years old) is constantly getting into trouble. One day an acquaintance convinces him that learning a Bible verse a month will help guide him through the temptations he faces and help him make wise decisions. The story tracks Frank’s progress for several months as he learns the Bible really can help him make good choices in his life.

It was that premise that inspired her to write three of her most popular children’s books. In Frank Hudson’s Hedge Fence, Frank (a boy of about ten or twelve years old) is constantly getting into trouble. One day an acquaintance convinces him that learning a Bible verse a month will help guide him through the temptations he faces and help him make wise decisions. The story tracks Frank’s progress for several months as he learns the Bible really can help him make good choices in his life.

We Twelve Girls is similar to Frank Hudson’s Hedge Fence. In this story, twelve young teenaged girls, all close friends at boarding school, are separated over the summer months; but they each pledge to learn a new verse every week and find a way to apply the verse to their lives. Over the course of the book, each young lady learns what it means to live a God-centered life according to the Bible.

We Twelve Girls is similar to Frank Hudson’s Hedge Fence. In this story, twelve young teenaged girls, all close friends at boarding school, are separated over the summer months; but they each pledge to learn a new verse every week and find a way to apply the verse to their lives. Over the course of the book, each young lady learns what it means to live a God-centered life according to the Bible.

Another example is A Dozen of Them. In this book, twelve-year-old Joseph has many challenges in his life; but he made a promise to his older sister he would read at least one Bible verse each month and make it a rule to live by. To Joseph it’s a silly promise—how can reading one Bible verse a month make any difference? But to his astonishment, Joseph begins to see changes in his own life and in the lives of those around him, all because of the verses he reads and memorizes.

Frank Hudson’s Hedge Fence and We Twelve Girls are both available as e-books on Amazon. A Dozen of Them was originally published in 1886 as a serial in The Pansy magazine, and we thought it would be nice to reproduce it on this blog, in the same serial format as the original.

Each week you can read a new chapter of A Dozen of Them here and here’s Chapter One:

A Dozen of Them

Chapter 1

And Thomas answered and said unto him, My Lord and my God.

He saith unto him, Feed my lambs.

If we walk in the light, as he is in the light, we have fellowship one with another, and the blood of Jesus Christ his Son, cleanseth us from all sin.

I am he that liveth, and was dead; and behold, I am alive forevermore.

Young Joseph sat on the side of his bed, one boot on, the other still held by the strap, while he stared somewhat crossly at a small green paper-covered book which lay open beside him.

“A dozen of them!” he said at last. “Just to think of a fellow making such a silly promise as that! A verse a month, straight through a whole year. Got to pick ’em out, too. I’d rather have ’em picked out for me; less trouble.

“How did I happen to promise her I’d do it? I don’t know which verse to take. None of ’em fit me, nor have a single thing to do with a boy! Well, that’ll make it all the easier for me, I s’pose. I’ve got to hurry, anyhow, so here goes; I’ll take the shortest there is here.”

And while he drew on the other boot, and made haste to finish his toilet, he rattled off, many times over, the second verse at the head of this story.

The easiest way to make you understand about Joseph, is to give you a very brief account of his life.

He was twelve years old, and an orphan. The only near relative he had in the world was his sister Jean aged sixteen, who was learning millinery in an establishment in the city. The little family though very poor, had kept together until mother died in the early spring. Now it was November, and during the summer, Joseph had lived where he could; working a few days for his bread, first at one house, then at another; never because he was really needed, but just out of pity for his homelessness. Jean could earn her board where she was learning her trade, but not his; though she tried hard to bring this about.

At last, a home for the winter opened to Joseph. The Fowlers who lived on a farm and had in the large old farmhouse a private school for a dozen girls, spent a few weeks in the town where Joseph lived, and carried him away with them, to be errand boy in general, and study between times.

Poor, anxious Jean drew a few breaths of relief over the thought of her boy. That, at least, meant pure air, wholesome food, and a chance to learn something.

Now for his promise. Jean had studied over it a good deal before she claimed it. Should it be to read a few verses in mother’s Bible every day? No; because a boy always forgot to do so, for a week at a time, and then on Sunday afternoon rushed through three or four chapters as a salve to his conscience, not noticing a sentence in them. At last she determined on this: the little green book of golden texts, small enough to carry in his jacket pocket! Would he promise her to take—should she say each week’s text as a sort of rule to live by?

No; that wouldn’t do. Joseph would never make so close a promise as that. Well, how would a verse a month do, chosen by himself from the Golden Texts?

On this last she decided; and this, with some hesitancy, Joseph promised. So here he was, on Thanksgiving morning, picking out his first text. He had chosen the shortest, as you see; there was another reason for the choice. It pleased him to remember that he had no lambs to feed, and there was hardly a possibility that the verse could fit him in any way during the month. He was only bound by his promise to be guided by the verse if he happened to think of it, and if it suggested any line of action to him.

“It’s the jolliest kind of a verse,” he said, giving his hair a rapid brushing. “When there are no lambs around, and nothing to feed ’em, I’d as soon live by it for a month as not.”

Voices in the hall just outside his room: “I don’t know what to do with poor little Rettie today,” said Mrs. Calland, the married daughter who lived at home with her fatherless Rettie.

“The poor child will want everything on the table, and it won’t do for her to eat anything but her milk and toast. I am so sorry for her. You know she is weak from her long illness; and it is so hard for a child to exercise self control about eating. If I had anyone to leave her with I would keep her away from the table; but everyone is so busy.”

Then Miss Addie, one of the sisters: “How would it do to have our new Joseph stay with her?”

“Indeed!” said the new Joseph, puckering his lips into an indignant sniff and brushing his hair the wrong way, in his excitement; “I guess I won’t, though. Wait for the second table on Thanksgiving Day, when every scholar in the school is going to sit down to the first! That would be treating me exactly like one of the family with a caution! Just you try it, Miss Addie, and see how quick I’ll cut and run.”

But Mrs. Calland’s soft voice was replying: “Oh! I wouldn’t like to do that. Joseph is sensitive, and a stranger, and sitting down to the Thanksgiving feast in its glory, is a great event for him; it would hurt me to deprive him of it.”

“Better not,” muttered Joseph, but there was a curious lump in his throat, and a very tender feeling in his heart toward Mrs. Calland.

It was very strange, in fact it was absurd, but all the time Joseph was pumping water, and filling pitchers, and bringing wood and doing the hundred other things needing to be done this busy morning, that chosen verse sounded itself in his brain: “He saith unto him, feed my lambs.” More than that, it connected itself with frail little Rettie and the Thanksgiving feast.

In vain did Joseph say “Pho!” “Pshaw!” “Botheration!” or any of the other words with which boys express disgust. In vain did he tell himself that the verse didn’t mean any such thing; he guessed he wasn’t a born idiot. He even tried to make a joke out of it, and assure himself that this was exactly contrary to the verse; it was a plan by means of which the “lamb” should not get fed. It was all of no use. The verse and his promise, kept by him the whole morning, actually sent him at last to Mrs. Calland with the proposal that he should take little Rettie to the schoolroom and amuse her, while the grand dinner was being eaten.

I will not say that he had not a lingering hope in his heart that Mrs. Calland would refuse his sacrifice. But his hope was vain. Instant relief and gratitude showed in the mother’s eyes and voice. And Joseph carried out his part so well that Rettie, gleeful and happy every minute of the long two hours, did not so much as think of the dinner.

“You are a good, kind boy,” said Mrs. Calland, heartily. “Now run right down to dinner; we saved some nice and warm for you.”

Yes, it was warm: but the great fruit pudding was spoiled of its beauty, and the fruit pyramid had fallen, and the workers were scraping dishes and hurrying away the remains of the feast, while he ate, and the girls were out on the lawn playing tennis and croquet, double sets at both, and no room for him, and the glory of everything had departed. The description of it all, which he had meant to write to Jean, would have to be so changed that there would be no pleasure in writing it. What had been the use of spoiling his own day? No one would ever know it, he couldn’t even tell Jean, because of course the verse didn’t mean any such thing.

“But I don’t see why it pitched into a fellow so, if it didn’t belong,” he said, rising from the table just as Ann, the dishwasher, snatched his plate, for which she had been waiting. “And, anyhow, I feel kind of glad I did it, whether it belonged or not.”

“He is a kind-hearted, unselfish boy,” said Mrs. Calland to her little daughter, that evening, “and you and mamma must see in how many ways we can be good to him.”

Next week: Chapter 2