This is the second of two posts about Isabella’s most difficult year. If you missed the first post, you can read it here.

In the spring and summer months of 1924, Isabella and her family carried on without her beloved husband, Ross, who died in March of that year.

The influenza epidemic that precipitated Rev. Alden’s death had waned, but there were still reported cases as late as the summer of 1924. That’s when Isabella’s sister Marcia fell ill.

Again a doctor was called to the house in Swarthmore to treat her, but the virus had weakened her heart. On August 7, Marcia succumbed to myocarditis, a rare but serious condition that causes inflammation of the heart muscle.

It had to have been a devastating blow to Isabella. For their entire lives, she and Marcia had been close. Marcia was the sister who tended Isabella when she was young, who watched over her when she was ill, and prayed that Isabella would choose Christ as her Saviour (you can read more about that here). Marcia helped introduced Isabella to her husband Ross; and after Isabella married, the Livingstons and the Aldens shared a home in Florida, and lived as neighbors at Chautauqua. They were as close as sisters could be.

Isabella wrote:

I held the dear hand of my one remaining sister Marcia all that day, and prayed for one more clasp of it, one look of recognition, all in vain. She went, as did my dear husband, without a word or look.

Marcia was laid to rest in Johnstown, New York; that was where Marcia and Isabella grew up, and where Marcia met her husband Charles (you can read more about that here). Her grave is beside Charles’ grave and the grave of their infant son Percy.

Although there’s no known record of it, Isabella, Grace, and other family members may have traveled to New York for the interment. If they did make the journey, it’s probable that Isabella’s son Raymond did not accompany them.

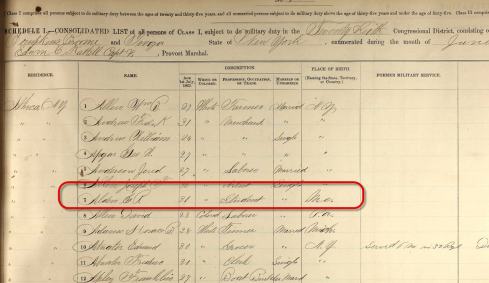

By the time Marcia died, Raymond was receiving medical care in Philadelphia for a chronic condition. All his life Raymond endured a painful form of eczema that caused open sores and blisters, leaving him prone to infection. In May of 1924, Raymond’s condition became worse, and he began to regularly see a doctor in Philadelphia.

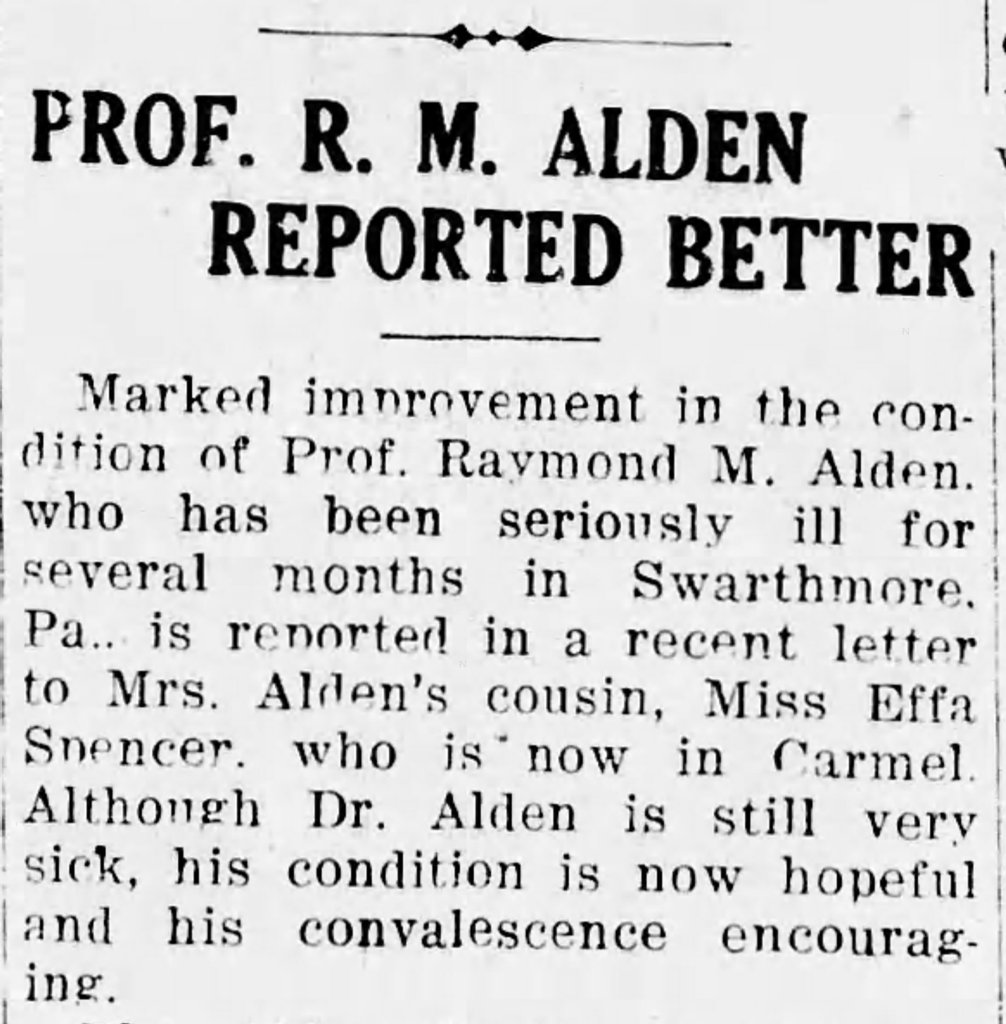

By July Raymond’s wife Barbara wrote to her cousin about Raymond’s health, saying that although he was still very sick, he had shown “marked improvement.”

But his improvement was short-lived. By September Raymond was suffering from an infection and, possibly, from an allergic reaction to medications he was given.

On September 27, less than two months after the death of his aunt, Raymond Alden died. Isabella was with him at the end.

“Mamma, fan me!” was the quick eager word my dear boy said, and the next minute he was gone.

Grace later wrote:

My saintly uncle went first, then my precious mother, and then my brilliant cousin, Dr. Raymond M. Alden. One blow after another that nearly crushed us all.

The family held a private funeral service for Raymond in Philadelphia; then it was time for the Aldens to leave Swarthmore and return to their Palo Alto home. Grace described it this way:

Then my dear aunt, courageous and wonderful through it all, went back to her California home with her brave daughter-in-law, and her five grandchildren.

There must have been times when Isabella felt the acute loneliness of losing the three most important people in her life. She once wrote to Grace:

There is no one in all the world who needs me any more. I’m too old to help anybody in any way, and too weak to be anything but a burden to those who have already more than they can bear. Why can’t I go now to my eternal rest? Does it seem to you wrong to pray for this?

There were other times when she spoke of the many family members who had died over the years, and asked impishly, “What do they think of us all by this time? Do they meet together and talk us all over?” She thought often of the loved ones who had “gone ahead” and wrote to Grace:

Sometimes I have to put my hands over my eyes in the darkness and say: “Casting all—All—ALL your care upon Him.” Oh, why doesn’t He take me home?”

But God did not call her home. Isabella lived with Barbara and her grandchildren in the house she and Ross built on Embarcadero Road in Palo Alto for another six years.

By all accounts, Barbara was loving and kind and “more than a daughter” to Isabella. And despite Isabella’s belief that she was “too weak to be anything but a burden” to Barbara, she would soon find that her work on Earth was not done, and that she had one last novel to write before she would be called Home to her Saviour.

Next Month: Isabella’s Final Novel

You can read more about the house Isabella and Ross built in Palo Alto by clicking here.