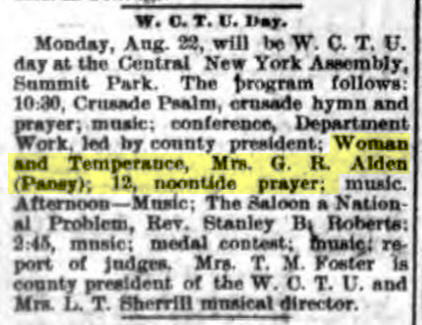

For more than a quarter of a century, Isabella edited newspapers (like The Pansy), wrote innumerable novels and short stories, taught classes on homemaking and child rearing, served congregations as a pastor’s wife, and designed Sunday school lessons for children. In between all that, she somehow managed to travel extensively.

Sometimes she was called upon to deliver an address at a conference. Other times she was the guest of a ladies’ missionary society or Bible study, where she often read chapters from one of the stories or novels she was working on at the time. (You can read more about that here.)

When she returned home from one of her many trips, her family gathered around her so she could tell them all about the places she went and the people she met. Her niece, Grace Livingston Hill wrote:

“She saw everything, and she knew how to tell, with glowing words, about the days she had been away so that she lived them over again for us. It was almost better than if we had been along, because she knew how to bring out the touch of pathos or beauty or fun, and her characters were all portraits. It listened like a book.”

One time in particular, Isabella returned home with an extraordinary story. Speaking at the same event had been a woman who was active in many of the same efforts that were of interest to Isabella, such as woman’s suffrage, and the temperance movement. Like Isabella, the woman was well known across the country as a writer and as a much-in-demand public speaker. It was this woman who recounted to Isabella an incident that happened to her.

With the woman’s permission (and with a promise to keep the woman’s identity a secret), Isabella wrote a short story based on the woman’s experience.

The premise of the story is this: A woman traveling by train to a speaking engagement notices an older man and younger woman traveling together on the same train. She quickly realizes she had come upon a couple in the middle of an elopement—and that the young would-be bride is having second thoughts!

How Isabella’s friend intervened (and what happened after) were recounted in Isabella’s story. When it was finished, Isabella sent the story off to a Christian newspaper that was pledged to publish a certain number of her stories each year.

To her surprise, the editor wrote back to ask Isabella if she had considered that the story might suggest to young people “evil ways of which they had never read.”

Can you imagine that? The editor actually worried that Isabella’s story about an elopement might have a negative or “evil” influence on the young people who read it!

In the end, Isabella withdrew the story, locked it away, and forgot all about it. Then, in the late 1920s, she came across the old manuscript and decided to expand the story into a novel.

The result was An Interrupted Night, and the story’s lead character of Mrs. Mary Dunlap was based on Isabella’s friend and the unusual events she told Isabella about decades before.

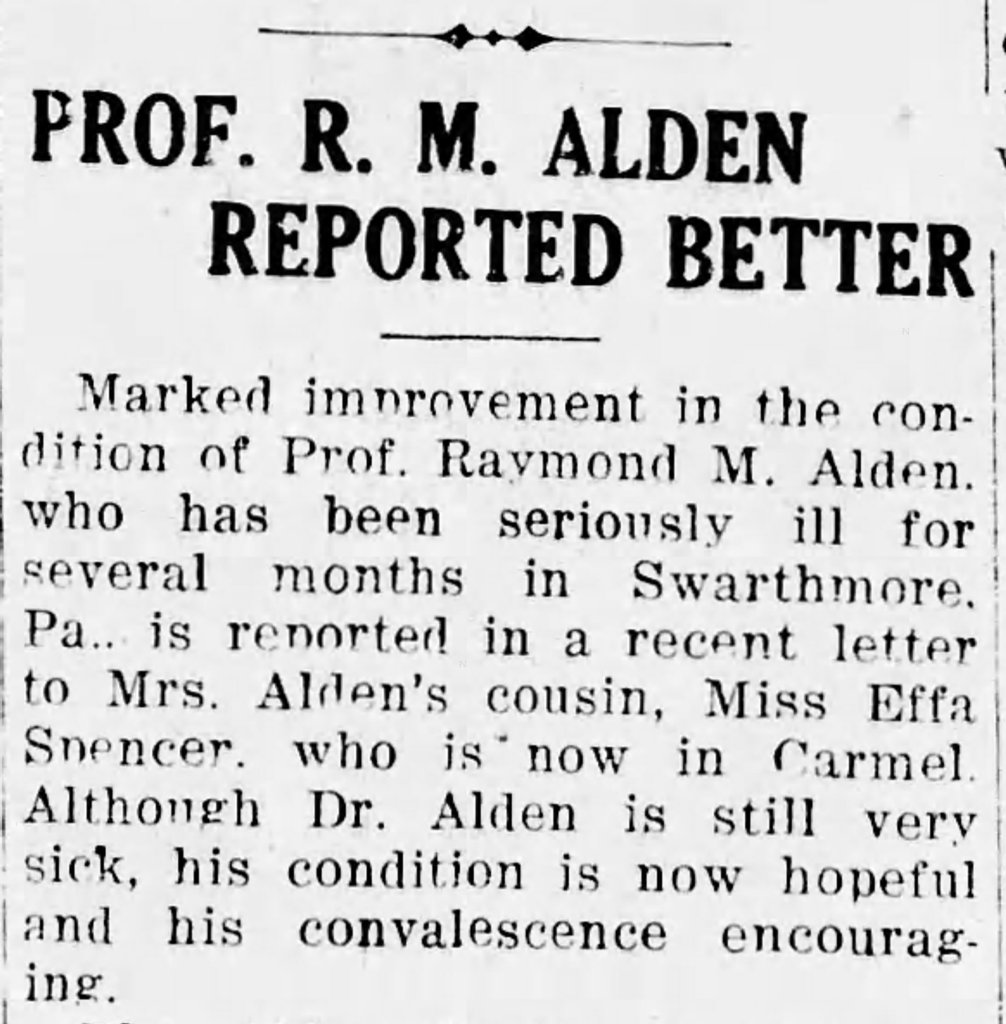

By the time she finished writing the book and submitted it to a publisher, Isabella was in frail health. When the publisher asked her to make some edits to her manuscript, Isabella’s niece, Grace Livingston Hill, stepped in to help her “put it into final shape.”

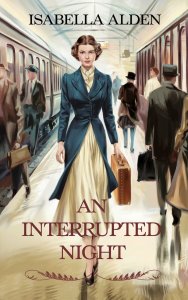

The book was released in the fall of 1929 with a decidedly modern-looking cover:

And it was received by a decidedly modern audience that took the story’s premise of an eloping couple in stride. Isabella later wrote that she “exploded with laughter” when she thought about how much the world had changed in the years since she first wrote the story.

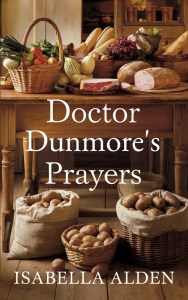

Now An Interrupted Night is available for twenty-first century readers to enjoy with a brand new cover:

Mary Dunlap is on her way to a speaking engagement when the train on which she travels experiences engine trouble and must make an unexpected stop for the night. While frustrated by the delay, Mrs. Dunlap quickly realizes a couple on the train is in the middle of an elopement—and the would-be bride is having second thoughts! Drawing on God’s strength, Mrs. Dunlap intervenes; but can she convince the young woman to abandon her plan and return home to her mother before it’s too late?

An Interrupted Night is now available from The Pansy Shop, along with novels by Rev. Charles M. Sheldon, Mary McCrae Culter, and other Christian authors in Isabella’s circle of family and friends. Click on the tab in the menu above, or click here to check out The Pansy Shop!

BY THE WAY …

Who do you think was the “real” Mrs. Mary Dunlap? Frances Willard or Emily Huntington Miller Perhaps Harriett Lothrop (who wrote as “Margaret Sidney”)? Leave your guess in the comments below!