Isabella didn’t have television or electronic devices during her lifetime (even radios weren’t common in homes until the 1930s). So on long cold winter days and evenings, when people had to stay indoors out of necessity, they had to come up with ways to entertain themselves.

Then, as now, board games like chess, checkers, and backgammon were popular; but they limited play to only two people. What was a family to do to pass the time?

Family members often read aloud to each other (click here to read more about Isabella’s skill at reading aloud) or joined together to sing hymns or popular songs.

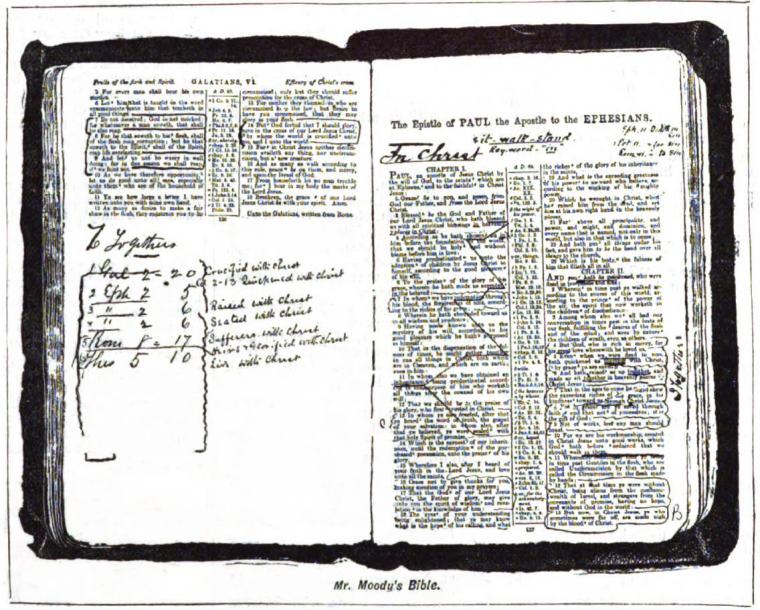

Newspapers and magazines published word games, and families often joined together to solve riddles like this:

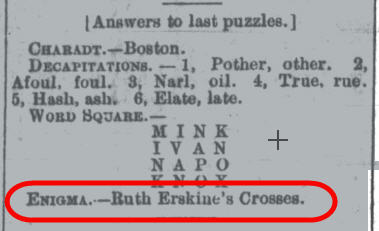

Or this word scramble from a 1907 magazine:

(Scroll to the bottom of this post to see the answers to these two puzzles.)

But when friends came to call, or neighbors got together, playing parlor games was the most common way for people to pass those cold winter evenings.

The rules for most games were simple, and the games could accommodate any number of players, so they were ideal for entertaining children and adults. Here are a few parlor games that were in vogue during Isabella’s lifetime:

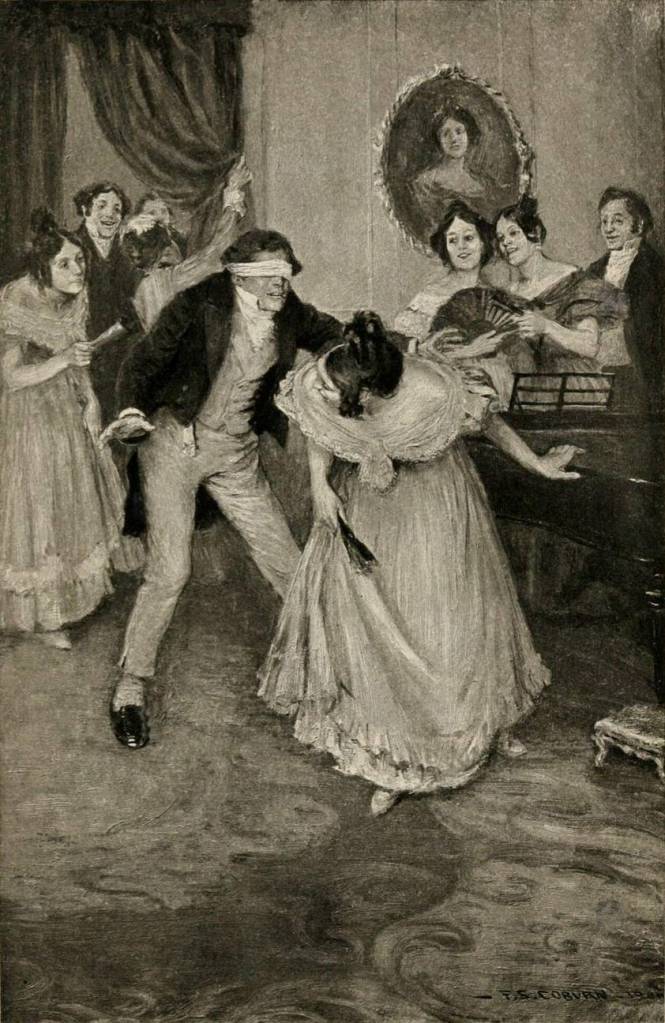

Blind Man’s Bluff:

Versions of Blind Man’s Bluff have been around since ancient Greece. The rules were simple; players were confined to a single room or space; one player was blindfolded and roamed the room/space freely, trying to catch one of the players. Once a player was caught, the “blind man” had to correctly identify him or her in order to win the round.

Savvy parents and alert chaperones usually limited this game to children, because teenagers and adults too often used it as a thin excuse to lay hands on each other.

Isabella hinted at Blind Man’s Bluff in her novel, As in a Mirror, when teenaged Elfrida Elliott snuck out of her parents’ house to join a group of friends for a night of games:

Very foolish games they seemed to be for the most part, having the merest shred of the intellectual to commend them, and that so skillfully managed that the merest child in intellect might have joined in them heartily. But the distinctly objectionable features seemed to be connected with the system of forfeits attached to each game. These, almost without exception, involved much kissing. Of course the participants in this entertainment were young ladies and gentlemen. There seemed to be a certain amount of discrimination exercised by the distributor of the forfeits, yet occasionally such guests as “Nannie” and “Rex” and others of their class would be drawn into the vortex, and seem to yield, as if to the inevitable, with what grace they could. [There was] a laughing scramble between the said Nannie and an awkward country boy, who could not have been over fifteen. He came off victorious, for she rubbed her cheek violently with her handkerchief, and looked annoyed, even while she tried to laugh.

Pass the Parcel:

A favourite game for all ages was Pass the Parcel. Here’s how it’s played: a small object is wrapped in multiple layers of paper or cloth, and passed around the circle to music. Each time the music stops, the person caught holding the parcel gets to remove one layer of wrapping. The win goes to the first person who can correctly identify the object before it is unwrapped; or to the person who ultimately removes the final wrap to reveal the object.

Wink Murder:

Another favorite was Wink Murder. To play, everyone sits in a circle and closes their eyes, while one person walks around the circle of players, choosing a murderer by tapping him or her once on the head. They then choose the detective by tapping a player twice on the head.

The players then open their eyes and engage in conversation, while the detective moves to the center of the circle and is allowed three tries to guess who the murderer is. Meanwhile, the murderer “kills” the other players by making eye contact and winking at them, trying not to be caught by the detective in the process.

To add to the fun, the victims “die” dramatically before they leave the circle. If the detective doesn’t identify the murderer in three attempts, he or she remains detective for the next round. If the detective guesses correctly, the murderer becomes the detective for the next round.

Have you played any of these parlor games before? What are your favorite games to play with your family, friends, or church group?

The answer to the word riddle is: Vowels

The answer to the word scramble is: Misunderstood