At the height of her popularity Isabella’s books were published in several languages and sold all over the world.

She had a large fan base in England, and in the 1890s a British publisher took the unusual step of publishing Isabella’s novels as pamphlets. Today, we’d call them paperback books.

S. W. Partridge & Co. of London advertised the books as “Partridge’s Cheap Pansy Series.” Each edition included a list of the available titles in the series:

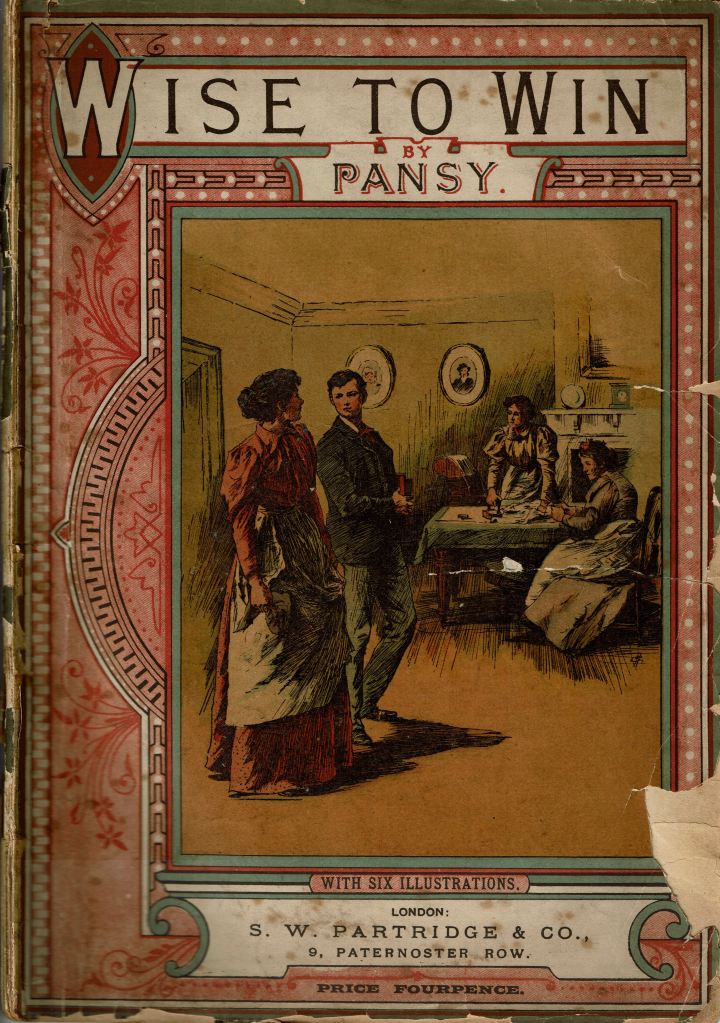

The novels measured 7-1/2” by 10-3/4”, making them slightly smaller than the 8-1/2 by 11” standard paper Americans use today. They were only 64 pages long, but thanks to their 2-column layout and small type, each novel was complete and compact enough to fit into a lady’s bag.

In fact, Partridge & Co. published them particularly for women travelers. They were sold at newsstands in railway stations throughout England and cost just four pennies.

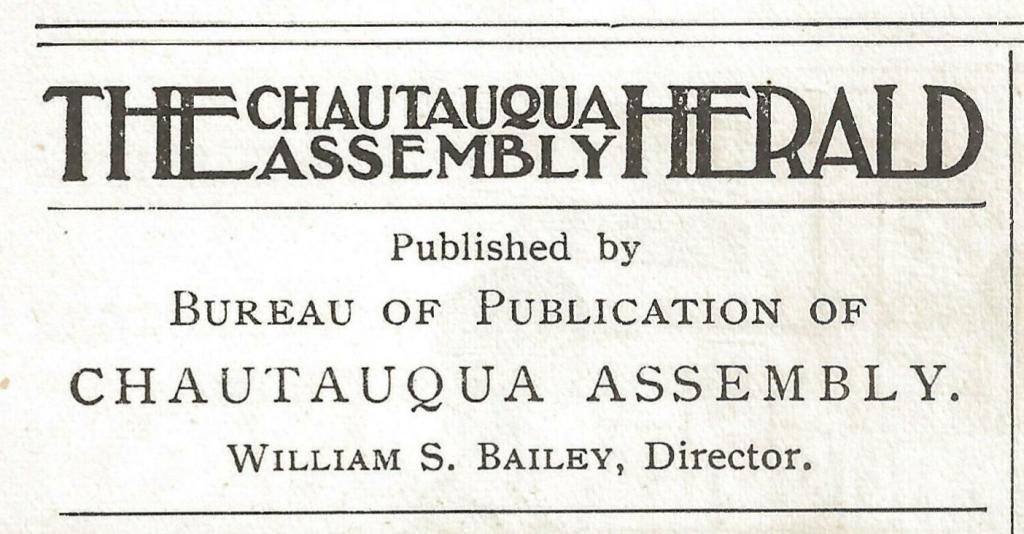

Each book featured a beautifully embellished, full-color cover that illustrated a particular scene from the story. Here’s the cover for Chautauqua Girls at Home:

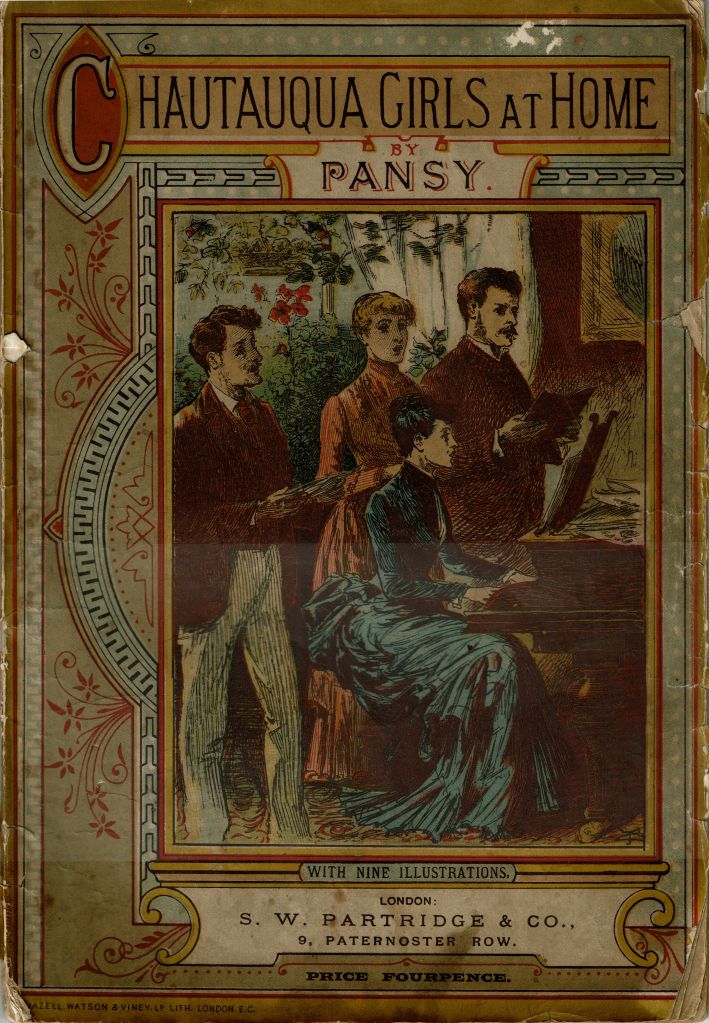

The cover art for Ruth Erskine’s Crosses shows the moment Ruth’s father introduced her to Judge Burnham.

What do you think of the depiction of this important scene? Is that how you pictured Judge Burnham when you first read Ruth Erskine’s Crosses?

The cover for Julia Ried shows the moment Julia went to apply for the bookkeeping job at the box factory.

In addition to the cover, each book had anywhere from five to nine black and white illustrations. This one, in Julia Ried, depicts the moment Dr. Douglass introduced Julia to Mrs. Tyndale.

Mottos were very popular in the 1890s, and this motto appeared at the end of Julia Ried:

It very nicely sums up one of the lessons Julia learned in the story.

Often, mottoes like this one were used as inexpensive sources of artwork. Ladies cut them from the pages of books and magazines and pasted them into scrapbooks or framed them to hang on the wall.

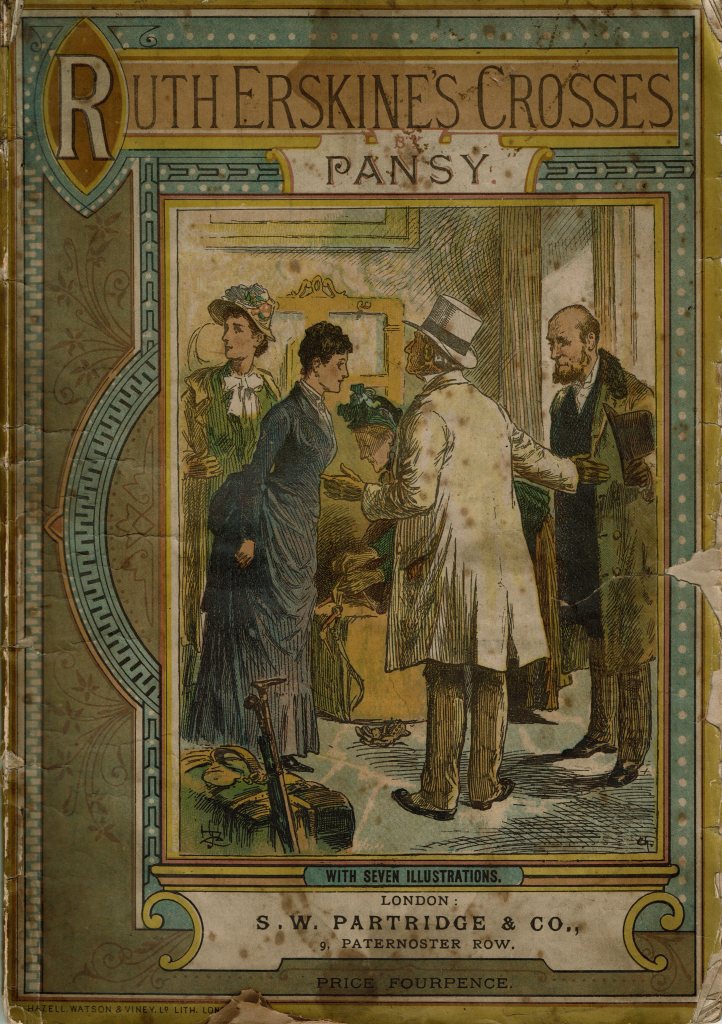

Ester Ried Yet Speaking also ends with a motto related to the story:

The cover for Interrupted illustrates the moment Claire Benedict learned her father’s money was gone and the family was bankrupt.

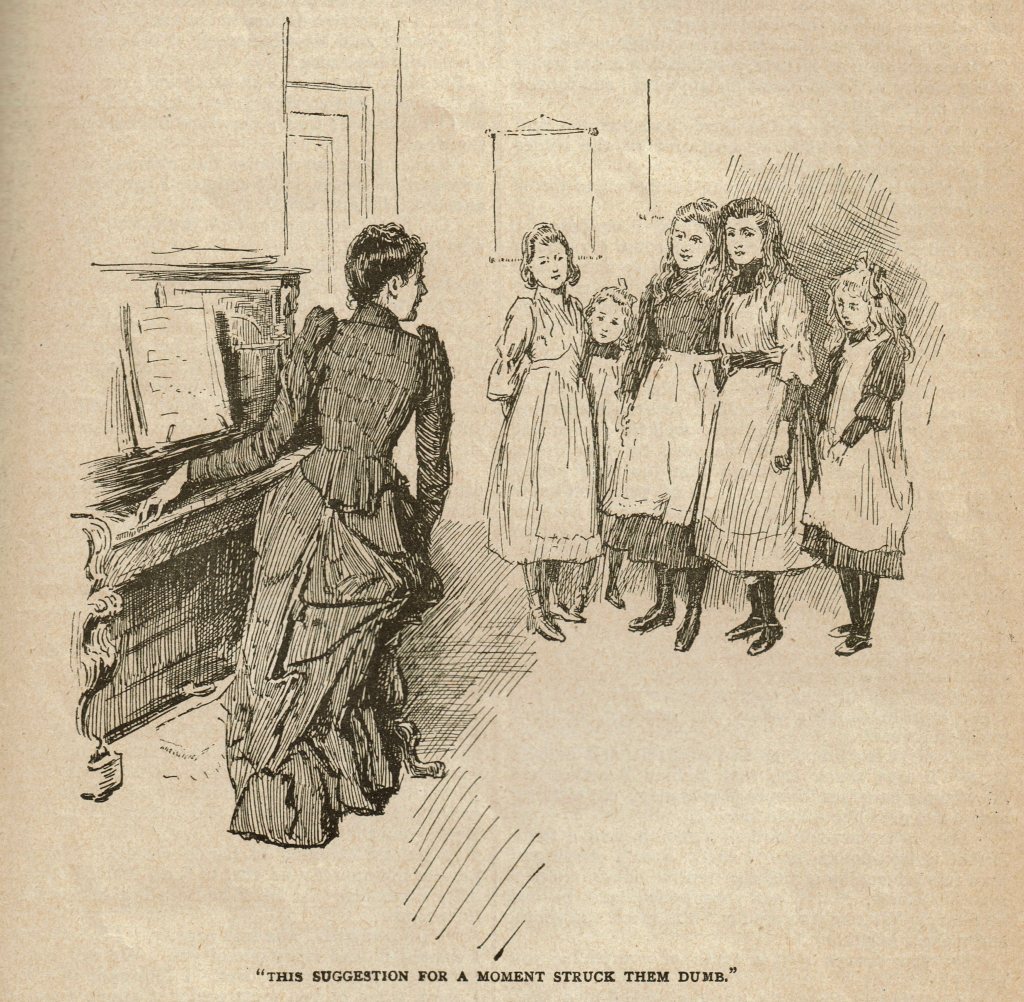

One of the black-and-white illustrations shows the moment Claire suggests to her students that they take on the job of cleaning up the church sanctuary:

It wasn’t uncommon for the titles of Pansy’s novels to be changed when they were published in other countries. One Commonplace Day was one such novel; in England it was renamed Wise to Win:

These paperback books all have some wear and tear, but considering the fact that they’re over 130 years old, they are in remarkably good shape. Perhaps they’ll last another hundred years for a new generation of Pansy readers to enjoy!

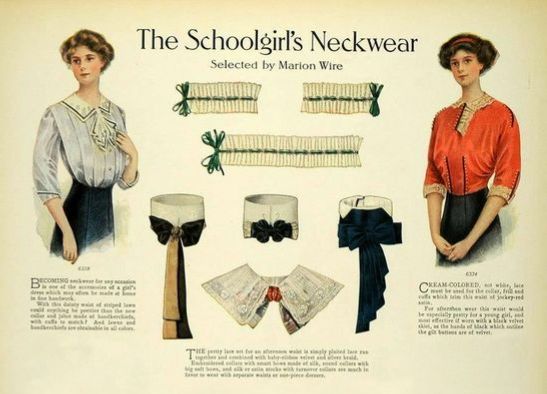

!["A Fisherwoman's Hem." How can I lengthen a seven-gored dark blue serge skirt? Are hip yokes fashionable? [signed] Amateur.

It is not practicable to lengthen a skirt by adding a yoke. I should suggest that you add a "fisherwoman's hem" of dark blue chiffon broadcloth, if you cannot match your serge.

The advice is accompanied by an illustration of a young woman dressed in shirtwaist and floor-length skirt standing before a full-length mirror.](https://isabellaalden.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/lengthen-a-skirt_ladies-home-journal_mar-1906-b.jpg?w=882)