It’s hard to imagine a world without Isabella Alden’s wonderful books and stories; but, left to her own devices, Isabella never would have become a published writer.

From a young age she had been taught to let her imagination soar. She began keeping a diary at the age of six, filling it with records of daily events and bits of stories. And even before she could write, Isabella’s mother encouraged her to make up little stories—perhaps from a picture Isabella would show her, or out of a few toys or some flowers. “Make a story out of it for mother,” was a most familiar sentence.

Out of those beginnings, Isabella developed her writing skills, and she continued to craft stories for the amusement of her friends and family. Her talent showed in school assignments, too; her compositions always earned good grades and won her recognition and prizes.

It was at school that Isabella Alden met her good friend, Theodosia Toll, nicknamed Docia. They were students together at Oneida Seminary in New York. After they graduated, Isabella returned to the school as a teacher; and since Docia’s family home was nearby in a neighboring town, the young women saw each other often.

After the close of one particular school year, Docia arrived to help Isabella pack up her things. Isabella was leaving the next morning to spend the long vacation at her family’s home, some eighty miles away.

After the close of one particular school year, Docia arrived to help Isabella pack up her things. Isabella was leaving the next morning to spend the long vacation at her family’s home, some eighty miles away.

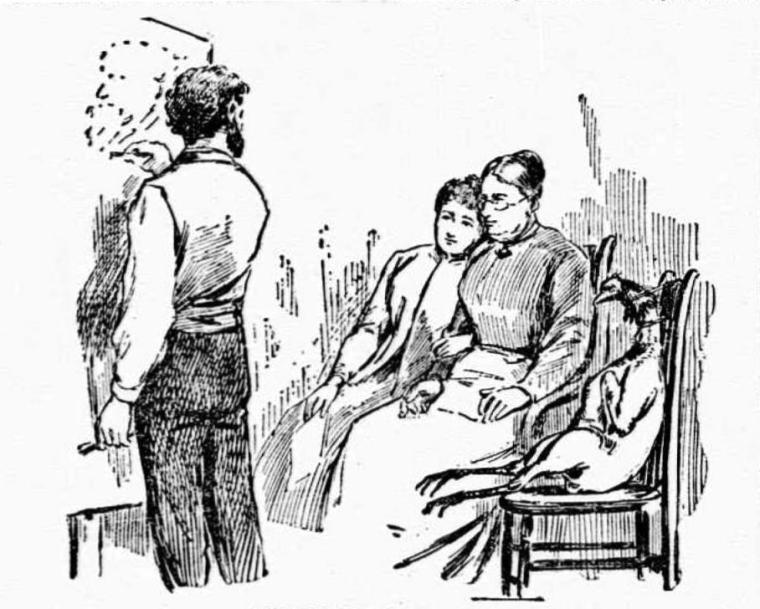

While Isabella packed, she tasked Docia with sorting through the papers and books she had stored in a large trunk. As Docia went through the trunk, she came across a story Isabella had written as an entry for a writing contest. Here is Isabella’s description of what happened next:

“Why, Belle!” she suddenly exclaimed. “Here is that story you were to send to Cincinnati! Didn’t you do it after all?”

“No, I didn’t,” I said.

“But you promised!”

“No, not exactly. I said I would, if I didn’t change my mind, and I changed it.”

“Well! I think you were a perfect simpleton! It might have taken the prize. I thought it was the best thing you had written. What do you want done with it? Oh, say! Don’t you believe! The time for sending manuscripts isn’t up yet! Here is the printed slip that tells about it. There are seven days yet. Now do be sensible and send it on. Just think what fun it would be if it should win the prize!”

Then I appeared in the doorway and spoke with decision.

“I’ll do no such thing. If I can’t write a better story than that, it proves that I ought never to write at all. Tear the thing into bits and throw it in the grate with the other rubbish. I’ll set fire to them tonight.”

Luckily, Docia saw the promise in that story and instead of tearing it to bits so it could be set on fire, she submitted it to the contest under Isabella’s name.

Two months later, Isabella was shocked to receive a letter from the Western Tract & Book Society in Cincinnati, congratulating her on her win. Enclosed with the letter was a check for fifty dollars!

Two months later, Isabella was shocked to receive a letter from the Western Tract & Book Society in Cincinnati, congratulating her on her win. Enclosed with the letter was a check for fifty dollars!

After she got over the initial shock of winning a prize for a story she thought she had burned, Isabella realized that Helen Lester was something to be proud of—especially once the contest judges explained the reason the story won:

“In the opinion of the carefully chosen committee of award, it met the condition imposed by the grand old Christian gentleman who offered the prize. It was to be given for the manuscript that would best explain God’s plan of salvation, so plainly that quite young readers would have no difficulty in following its teachings if they would, and so winsomely that some of them might be moved to take Jesus Christ for their Saviour and Friend.”

And how did Isabella spend that fifty-dollar prize money? She made two packets, each containing “the enormous sum of twenty-five dollars.” She placed one of the packets inside a bound volume of her first book, Helen Lester. On the fly leaf she wrote:

“Presented to my honored father.”

The second packet went into another copy of the book; and on the fly leaf she wrote:

“To my precious mother.”

Then, in both books she wrote those “wondrous words that must have trembled with excitement, and ought to have been written in capitals”:

“From the Author.”

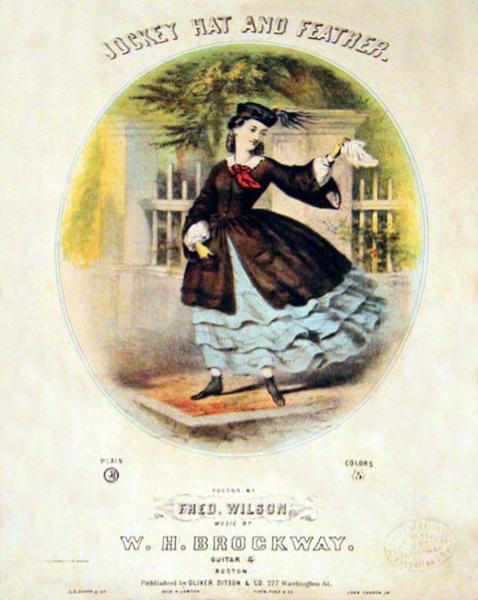

Helen Lester was published in 1865 and with it, Isabella’s writing career was launched. The following year she published another children’s book, Nanie’s Experiment; Jessie Wells was published in 1867, quickly followed by Tip Lewis and His Lamp. After that, she published multiple titles each year, demonstrating both her talent and her discipline as a writer.

Helen Lester was published in 1865 and with it, Isabella’s writing career was launched. The following year she published another children’s book, Nanie’s Experiment; Jessie Wells was published in 1867, quickly followed by Tip Lewis and His Lamp. After that, she published multiple titles each year, demonstrating both her talent and her discipline as a writer.

Since then, her stories that explain salvation through Christ and the rewards of abiding faith in God have enlightened and entertained generations of readers around the world.

You can read Helen Lester for free. Click on the cover to begin reading.

You can learn more about Isabella’s friendship with Docia by clicking here.

.