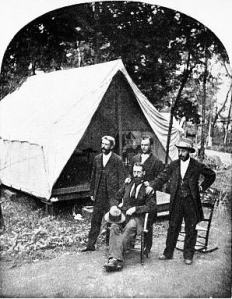

The Chautauqua Institution was constantly evolving and improving. From its humble beginnings as a camp-meeting for the purpose of educating Methodist Sunday School teachers, it grew into an esteemed and respected institution of general education for anyone willing to take on the curriculum and abide by Chautauqua’s basic principles. Over the course of several decades, buildings were erected and dismantled; surrounding acres were acquired; and landscapes changed.

Isabella Alden wrote about Chautauqua’s transformations in Four Mother’s at Chautauqua. When Flossy, Eurie, Marian and Ruth stepped off the steamer onto Chautauqua’s dock in 1913, they gazed about in wide-eyed wonder.

“It isn’t the same place at all!” was Mrs. Roberts’s final exclamation. “Marian, don’t you remember the mud we waded through on that first night? We must have gone up that very hill, only, where is the road? Look at those paved streets! The idea! What is the name on that large building over there?”

“That’s the arcade,” volunteered a brisk young man who was looking out for possible boarders. “The jewelry store is there, and the art store; and all sorts of fancy-work classes meet there.”

“Fancy-work classes!” repeated the dazed little woman. “Who imagined such frivolities at Chautauqua!”

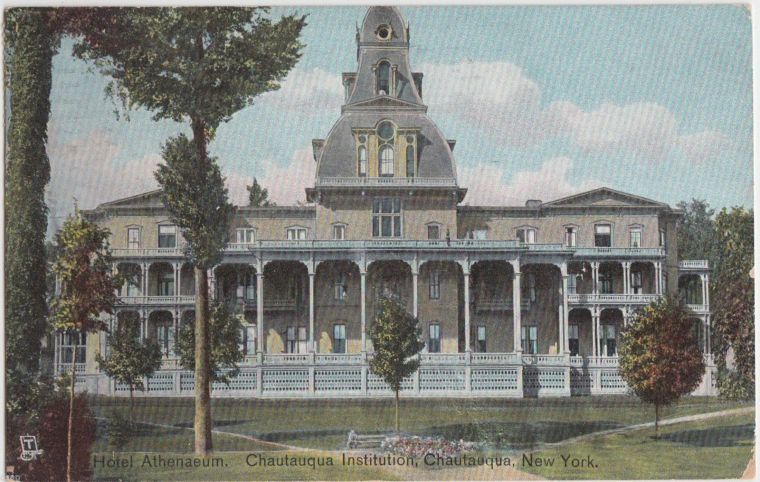

Mrs. Dennis laughed. “You will have to accustom yourself to more startling changes than those,” she said. “Aren’t we all going to a hotel for the night? Imagine a hotel of any sort at Chautauqua! I confess I had some fears lest it should not be large enough for our party, but those houses in the distance reassure me. Do you remember the dining-halls and the man who told us which ever one we went to we should wish that we had taken the other?”

“I wonder where they were located?” said Mrs. Burnham. “One was on a hill, I remember; the hill must be here still, but I don’t seem to recognize even hills.”

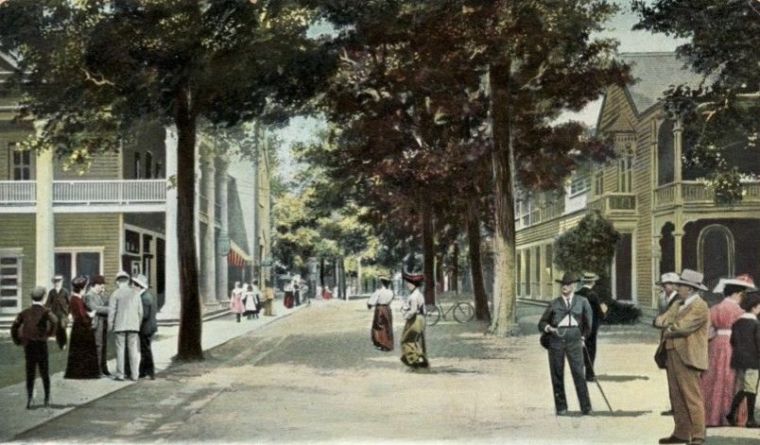

Many things had changed since the girls’ first visit. By 1921 there were six to eight hundred all-year residents on the Chautauqua grounds; the summer session lengthened from twelve days to fifty; and Chautauqua’s summer population swelled to the thousands. But whether resident, worker or visitor, everyone who entered Chautauqua’s grounds had one thing in common: they had a ticket.

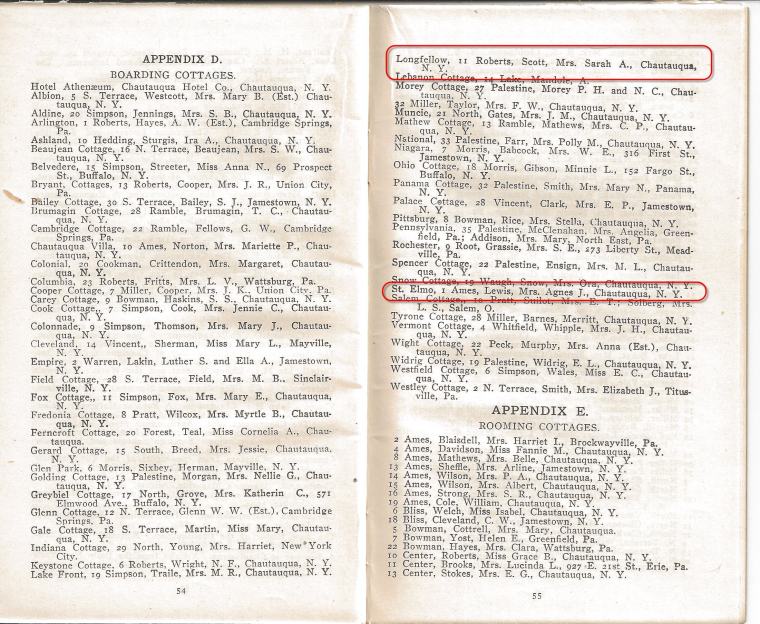

Before the Assembly opened each summer, every family had to obtain tickets. The only exceptions to the rule were children under the age of 9 and bedridden invalids. Even those who leased property on the grounds had to have tickets to enter and exit the grounds. Ticket prices were nominal, as illustrated in this table of charges from 1908:

On Sundays the gates were closed. No one was allowed to enter or exit on Sunday with one notable exception: Sunday passes were issued to any members of churches not represented at Chautauqua who wished to attend services in nearby Jamestown. Otherwise, Sunday passes could only be obtained in emergencies.

Once you were inside the gates, you had free access to the grounds and most classes or lectures. A map like this one from 1874 helped visitors navigate the streets and get to lectures on time. Click on the image for a larger view.

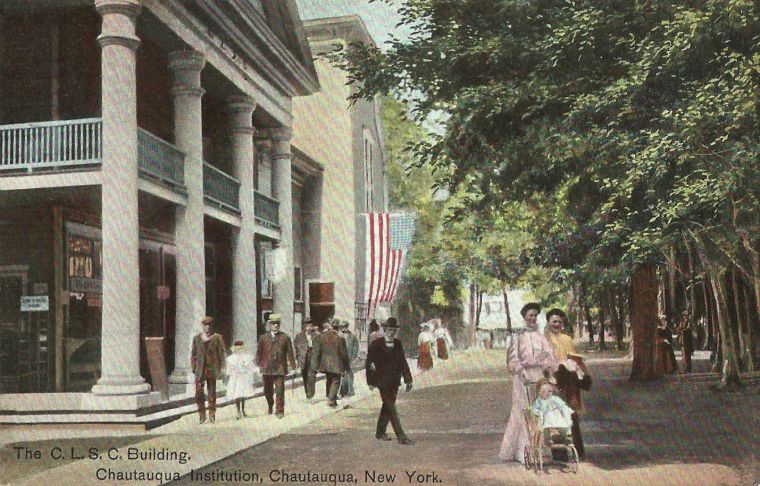

Isabella Alden incorporated many of the Chautauqua Institution buildings and locations in her novels. Her descriptions were so vivid, it isn’t hard to imagine how the buildings looked in their natural, woodland settings. Here are some of the buildings and settings Isabella wove into her stories; many of them are marked on the 1874 map.

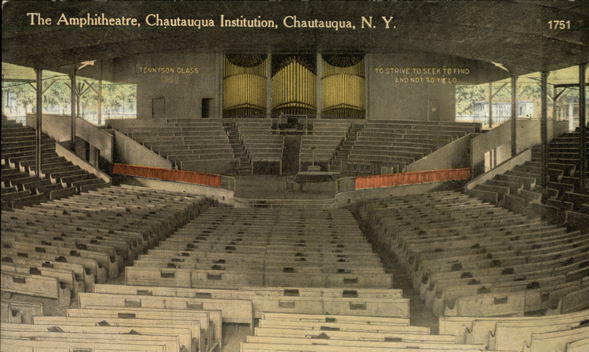

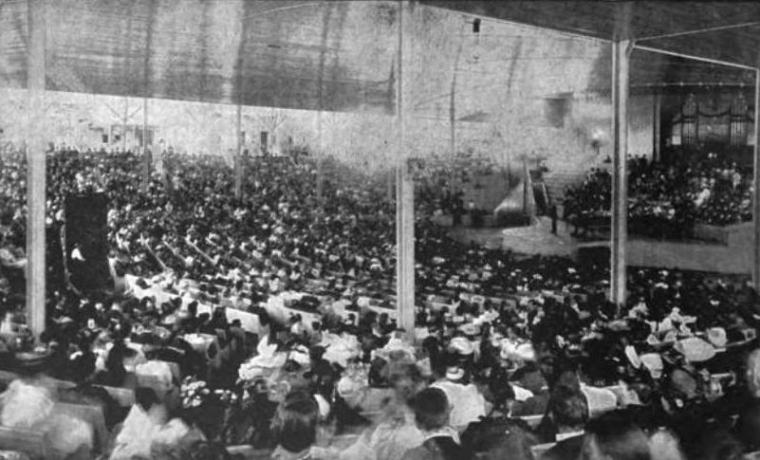

Amphitheater. Located at the intersection of Clark and Waugh avenues, this remodeled venue seated almost 6,000 people. The choir gallery had seats for 500. In 1907 the Massey Memorial Organ was installed. Under the choir-loft and on either side of the organ were the Department of Music classrooms and offices.

Amphitheater. Located at the intersection of Clark and Waugh avenues, this remodeled venue seated almost 6,000 people. The choir gallery had seats for 500. In 1907 the Massey Memorial Organ was installed. Under the choir-loft and on either side of the organ were the Department of Music classrooms and offices.

Arts and Crafts Building. On Vincent Avenue, this 1903 complex housed the Arts and Crafts School as well as shops. Henry Turner Bailey, who directed the Arts and Crafts School, was famous for delivering entertaining lecturing at the same time he drew pictures on the blackboard with both hands at once.

Bell Tower. Located at the Point beside the pier, the Miller Bell Tower was dedicated in 1911. The bells rang five minutes before the lecture hours and at certain times throughout the day. After the final bell each night, silence was supposed to reign across the grounds. It was near the Miller Bell Tower that Ruth first encountered Hazel crying near the shore in Four Mothers at Chautauqua.

Colonnade. Facing Miller Park from the intersection of Pratt and Morris avenues, the Colonnade was the business center of Chautuaqua. It housed the post office, a barber shop, a hair salon, a tea room, and various stores, including grocery, dry-goods, shoe, hardware and drug stores. Visitors approaching the Colonnade building from the right passed through a vine-covered pergola.

Golden Gate. The Golden Gate at St. Paul’s Grove was used once a year as part of the C.L.S.C. Recognition procession. No one was allowed to pass through the Gate except those who had completed a C.L.S.C. course of study. We’ll share more about the Golden Gate in future posts about the C.L.S.C.

Hall of Christ. This monumental stone and brick building sat at the corner of Wythe and South avenues. Created by Bishop Vincent, it was used as a chapel for meditation and prayer; and as a place of quiet, spiritual fellowship.

.

The Hall of Philosophy. Known as “The Hall in the Grove” to Isabella Alden fans, this structure, modeled after a Greek temple, was located in St. Paul’s Grove. It was a regular meeting place of the C.L.S.C. conferences and gatherings.

When Caroline Raynor first arrived at Chautauqua in the book, The Hall in the Grove, young Robert Fenton took her to see his favorite building.

“Now which way do you want to go?”

“Whichever way you are pleased to take me. I have not seen anything save what I couldn’t help looking at when we arrived.”

“Then I’m just going to take you to the Hall. The rest rush to the Auditorium first and rave over that. It is splendid, I suppose; large, you know, and makes one think of crowds and grand things. But I can’t imagine people enough here to fill it—not to begin! With the Hall, now, it is different; just a nice audience would fill that, and it is so white, and so—Oh, well! I can’t explain, only it’s nice, and you will like it. Some people don’t care about it much; but I know you will.”

“Thank you,” said Caroline, and her heart was smiling as well as her eyes. She understood the boy; imagined something of what he would have said if he could have expressed his feelings, and she understood and appreciated the delicately-sincere compliment.

“This is a lovely avenue that leads to your favorite building,” she said, as she turned back to look at the straight wide road they had traversed, lying clear-cut amid the shadows of the overhanging trees.

“Isn’t it!” declared Robert, with ever-increasing enthusiasm. “This is another thing I like so much—this avenue. I’ll tell you, Caroline, when it must be just grand, and that is in full moonlight. Ha! There it is!”

It is impossible to describe to you the delight that was in the boy’s tones as the gleaming pillars of the Hall of Philosophy rose up before him; something in the purity and strength, and quaintness, seemed to have gotten possession of him. Whether it was a shadowy link between him and some ancient scholar or worshipper I cannot say, but certain it is that Robert Fenton, boy though he was, treading the Chautauquan avenues for the first time, felt his young heart thrill with a hope and a determination, neither of which he understood, every time he saw those gleaming pillars.

In the Hall’s concrete floor are inserted tablets in honor of the C.L.S.C. classes that contributed toward construction of the building. This diagram shows where each tablet was inlaid. You can see the tablet for Isabella Alden’s class of 1887 near the lower left corner. Click on the image to view a larger version.

.

.

.

Kellogg Hall, at Pratt-Ramble-Scott-Wythe avenues, was erected in 1889. The Kindergarten Department, Ceramics Department and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union had headquarters here.

.

.

Palestine Park. Located on the shore of Lake Chautauqua near Miller Park, this model of old Palestine was constructed as a teaching tool to illustrate lessons from the Bible. Watch for more on Palestine Park in a future Tour of Chautauqua blog post.

.

Post Office. The Post Office was located on the same plaza as The Colonnade. It was in the post office that Burnham Roberts encountered the charming Hazel Harris in Four Mothers at Chautauqua.

.

This photo from 1913 shows the busy Post Office. The number of people strolling through the plaza hints that it may have been a convenient thoroughfare for going from building to building on the grounds.

.

.

There are many other places to explore at Chautauqua.

Next stop on our Tour of Chautauqua: Having fun.

1 the Miller Bell Tower was erected alongside the dock. It was built to commemorate the life and contributions of Chautauqua co-founder Lewis Miller. When the girls returned in 1913 (as described in Isabella Alden’s book, Four Mothers at Chautauqua), they would have seen the beautiful new bell tower as they approached the dock; and they would pass it as they stepped off the boat and entered the Institute grounds.

1 the Miller Bell Tower was erected alongside the dock. It was built to commemorate the life and contributions of Chautauqua co-founder Lewis Miller. When the girls returned in 1913 (as described in Isabella Alden’s book, Four Mothers at Chautauqua), they would have seen the beautiful new bell tower as they approached the dock; and they would pass it as they stepped off the boat and entered the Institute grounds.