Rebecca’s dress was entirely appropriate and becoming. She had gone out from her father’s house very well supplied with clothes, and her ability to re-make them herself had stood her in good stead, so that now her dress of fine black cloth, made severely plain, but with minute attention to details, became her well. So did the black felt bonnet, with its three stylish plumes, which she had herself dressed over.

from Wanted, by Isabella Alden, published in 1894

In her stories, Isabella often used the latest fashion to define a character’s financial and social status, and Rebecca Meredith’s outfit was an excellent example. Because her dress was plain and black, her bonnet “with its three stylish plumes” was the centerpiece of her outfit and called attention to her pretty face.

Bonnets with plumes were very much in style when Wanted was published in 1894. Women’s magazines, like Godey’s Lady’s Book and The Ladies Home Journal showed that hats were be made from a variety of materials—straw, for example, or stiffened fabrics like velvet—and that they were quite modest in size.

Though small, hats at that time were heavily adorned with ribbons, bows, artificial flowers and, most importantly, bird plumes.

Bird feathers were the most desirable decorative elements on a lady’s hat. In 1894 The Ladies Home Journal predicted that actual wings displayed on bonnets would be “all the rage,” while another magazine wrote that “almost every second woman one sees in the streets flaunts an aigrette of heron’s plumes on her bonnet.”

Milliners used feathers from egrets, hummingbirds, herons, and even song birds of all kinds as adornments.

The more exotic the bird, the more desirable their feathers; and the millinery industry was willing to pay top dollar to anyone who would supply them, no questions asked.

But some people did ask questions and raise alarms, after nature lovers in England and the United States discovered that some birds, like ospreys and egrets, were hunted so mercilessly, ornithologists feared they would soon be extinct.

In London, a Society for the Protection of Birds was formed. Members pledged to never wear feathers of any bird not killed for the purpose of food. Similar organizations were formed in Europe, Canada, and the U.S.

The public outcry began to pay off, as women around the world pledged to stop wearing hats with real bird feathers, and American lawmakers enacted state and federal laws to protect certain species of birds by banning them from use in hats and garments.

One bird that was exempt from protection was the ostrich, because its feathers could be harvested without killing the bird. So it was natural that the millinery industry would turn its attention to ostriches as a source for adornments.

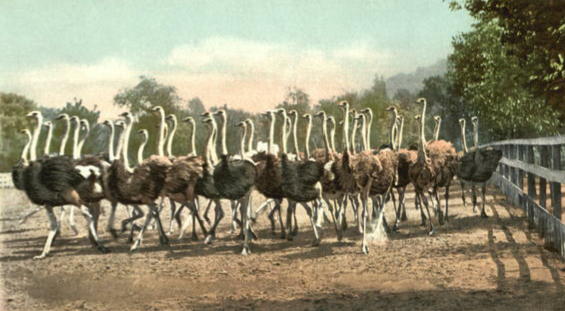

Ostrich farms that had been established in the southern United States in the late 1890s in hopes of selling feathers to the millinery industry suddenly saw an increased demand for their wares.

And because ostrich feathers could be plucked every eight or nine months, ostrich farmers with large herds enjoyed a regularly replenished inventory they could sell.

With the turn of the century, hat styles changed, and the small bonnets that were popular when Isabella wrote Wanted fell out of fashion. The new bonnet styles of the 1900s featured wide brims and brilliant colors.

Ostrich plumes suited the new styles beautifully. Because of their size, the plumes could cover a large hat’s crown and brim.

Even more importantly, ostrich feathers could be dyed to match almost any color. Women and conservationists rejoiced, feeling confident that they could use ostrich feathers for fashion without feeling guilty.

In her 1912 novel The Long Way Home Isabella made sure her fashionable characters wore the latest style in bonnets. Newlywed Ilsa Forbes wore a wide-brimmed hat when she boarded the train with her new husband Andy:

But Andrew had no words, just then; never was the heart of bridegroom more filled to overflowing, and he could not yet think about decorations or supper.

“My wife!” he murmured, as his arm encircled her. “Really and truly and forever my wife. Do you realize it, darling?”

She nestled as closely to him as her pretty, new traveling hat would permit and laughed softly.

There was, however, a problem with those stylish large hats adorned with ostrich feathers. In 1908 a letter to the editor of the Oregonian newspaper applauded the ban on exotic bird feathers, but raised a new and troubling concern about ostrich feathers:

The letter-writer wasn’t the only one wondering if an ostrich felt pain when its feathers were plucked. Soon the Audubon Society and other conservationists began asking the same question and took their findings to state legislators.

In California, where Isabella was living and where many of the country’s ostrich farms were located, the question was answered by lawmakers. In 1900 the state updated its penal code to make it a crime to intentionally mutilate or torture a living animal, which included plucking live birds like ostriches.

So ostrich farmers stopped plucking and began snipping feathers, instead. A 1911 article in the Dallas Morning News explained the process:

Once again, stylish ladies (and Isabella’s equally stylish characters) could wear hats adorned with feathers and maintain a relatively clear conscience.

It’s interesting how Isabella’s attention to details, like hat sizes and adornments, brought her stories to life. While she didn’t preach about fashion in her novels, she paid close attention to these niceties, and used them to bring authenticity to her characters and their world. Contemporary fans of her novels would have noted the subtle changes as keeping up with the times.

For us in 2025, it’s fascinating to learn there’s a whole complicated history behind Rebecca Meredith’s feathers—a history about women who were determined to write wrongs and find ways to be fashionable without compromising their conscience.

You can learn more about Isabella’s novels mentioned in this post by clicking on the book covers below:

Full disclosure: these are Amazon affiliate links, which means if you decide to purchase through them, this blog will receive a small commission. It doesn’t cost you anything extra, but it helps us keep this site running and researching Isabella’s life and the fascinating world in which she lived.