Category: Holiday Greetings

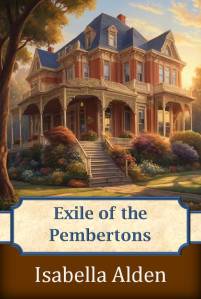

New Free Read: Exile of the Pembertons

This month’s free read is a short story Isabella wrote in 1898 for a popular Christian magazine. It’s the story of the Pemberton family and the difficult year they endured leading up to a 4th of July celebration.

Nettie Pemberton can hardly believe it: the family fortune is gone! Although she finds a job working for a kind family, Nettie watches long-time friends disappear from her life. Even Edward Field—whom Nettie has known and loved since childhood—seems to have forgotten her very existence. Now, as the Independence Day holiday approaches, Nettie must face another disappointment that may turn out to be more than her broken heart can bear.

YOU CAN READ “EXILE OF THE PEMBERTONS” FOR FREE!

Choose the reading option you like best:

You can read the story on your computer, phone, tablet, Kindle, or other electronic reading device. Just click here to download your preferred format from BookFunnel.com

Or you can select BookFunnel’s “email” option to receive an email with a PDF version you can read, print, and share with friends.

Why?

As a teacher and a parent, Isabella must have often found herself from time to time on the receiving end of a child’s relentless “Why?” questions. She probably understood that asking “Why?” is an important part of a young child’s learning process, and that it’s more than just a question; it’s a peek inside their busy minds, showing their natural drive to understand the world around them.

In many of the articles she wrote for The Pansy magazine, Isabella demonstrated how astute (and patient) she was in answering the many “Why?” questions she received from her young readers.

In 1891 she published this article that addressed children’s “Why?” questions about Easter:

“Why do people use eggs at Easter?”

“Why do they call a certain day in the spring Easter?”

“Why do Easter cards so often have pictures of butterflies on them?”

Let me see if I can answer your questions. Let me begin in the middle: “Why do they call a certain day in the spring ‘Easter’?”

Away back in the days when people had a great deal to do with imaginary “gods” and “goddesses,” there was one named “Ostara,” who was called the goddess of the spring; our fourth month of the year was set apart for her special service, and called “Eostur-monath,” or “Easter month.”

The heathen festivals in honor of Ostara were times of great rejoicing. The people were so glad that the season for the resurrection of flowers and vines and plants had come again, that they built great bonfires, and with wild shouts and many strange customs, showed their joy. They called it the “awaking of nature from the death of winter.”

After many years it became the custom for Christians to choose the same time of year for their festival in honor of the “awaking of Jesus from the death of sleep.” So that “Easter” today means to Christians the glad day when Jesus Christ arose from the grave.

Now for the second question:

“Why do people use eggs at Easter?”

That is an old, old thought handed down to us. When the festival was held entirely in honor of the return of spring, eggs seemed to be used as symbols of life. As from the apparently dead egg life sprang forth, after the mother hen had brooded over it for awhile, so from the apparently dead earth the life of nature started forth anew. This was the thought.

The Persians used the brightly-colored eggs as New Year presents in honor of the birth of the solar year, which, you know, is in March!

Christian people have held to the same symbol to represent their faith in the life after death. And in this connection I can best answer that third question about “butterflies.”

Did you ever watch a slow-crawling caterpillar with his awkward, woolly body and sluggish ways, and wonder how it was possible that such a creature could change into the brilliant butterfly, whose swift, graceful circlings through the air charm all eyes? If you have, I think you have answered your own question. Where could we find in nature a better symbol of the wonderful difference between these slow-moving, easily stopped, rather troublesome bodies of ours, and the glorious bodies promised us some day?

More than that, when the caterpillar weaves a coffin for himself and shuts himself into silence and immovableness, does it not seem as though his life was ended? Haven’t you had some such thought when you stood beside an open grave? How still and cold and utterly lifeless the body is which is being placed therein. Is it possible that it can live again?

“Oh, yes!” says the butterfly. “Look at me; I was a worm, and I crawled away and the children thought me dead. See me now! If God so clothe the worms of the dust, shall he not much more clothe you, O, ye of little faith?”

Almost as plainly as though he had a tongue, the bright-winged butterfly speaks to me.

A better emblem than the egg, I think it is, of the wonders of resurrection; but the egg is the universal emblem. Nearly all nations, and all classes of people, think a great deal about Easter eggs, and spend much time in making them beautiful. Isn’t it a grand thought that such simple, every-day objects are able to remind us of the glory which is to come to those who “love His appearing.”

Pansy.

What do you think of Isabella’s answers to the children’s “Why?” questions about Easter?

What is the most memorable “Why?” question a child ever asked you, and how did you answer?

Merry Christmas

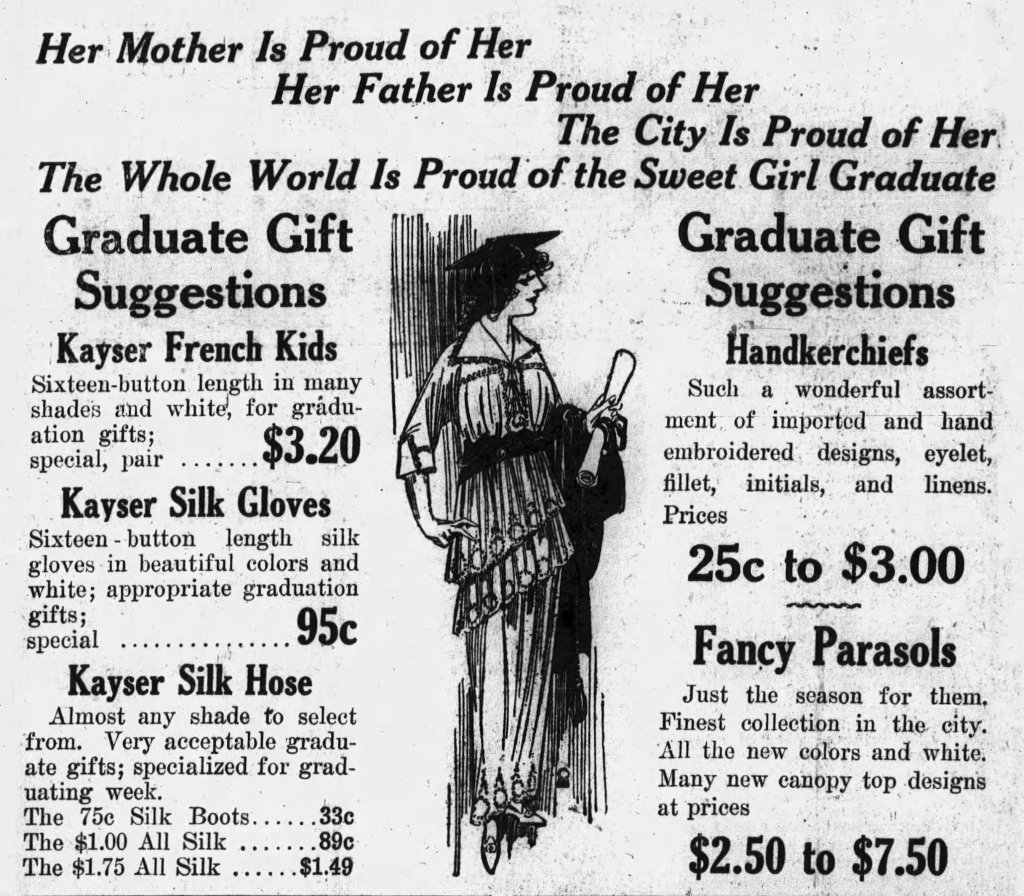

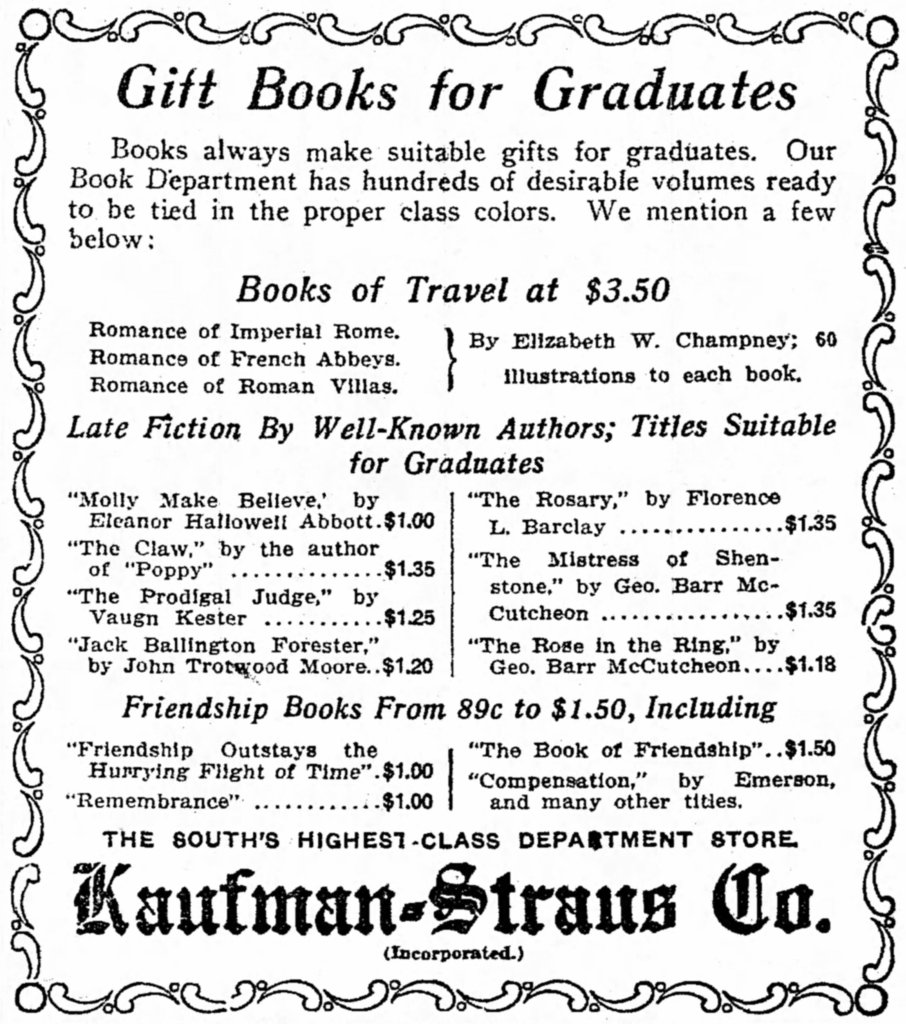

Graduation Time!

It’s that time of year, when students “commence” higher studies or the business of life. It’s the season for graduation ceremonies, when young men and women—as well as their parents—attend closing exercises of the school year, exchange cards of congratulations and bestow graduation gifts.

It was the same way in Isabella’s day. Being an educated woman, and having been a teacher herself, Isabella knew that graduation was a significant milestone in a young life. The characters she wrote about in her novels worked hard for their education, and they had good reason to celebrate their achievements.

Just as we do today, it was the fashion in the late 1800s and early 1900s to give graduates a gift of some kind to mark the occasion.

Acceptable gifts came in many forms. Boys and young men received neckties, gloves, fountain pens, and pocket watches.

Young women received watches, too; but instead of pocket watches, bracelet watches were in style, like the ones mentioned in this 1914 ad:

Stores carried a variety of gifts for the graduate, from handkerchiefs and gloves, to hosiery and stationery.

Stores also offered plenty of gift ideas that featured the latest in 1912 technology. The ad below mentions Kodak cameras and field glasses (binoculars) as desirable gifts for men and boys.

An ad in a 1916 issue of Good Housekeeping magazine suggested the gift of a table lamp, with a floral painted glass shade:

Lamps like that could be expenses; they cost anywhere from $15 to $50 each. For more budget-conscious gift-giving, books were always an appropriate option.

And if your taste didn’t run toward novels, Bibles and prayer books were an excellent choice, especially if the gift giver added a loving, hand-written message of congratulations on the fly leaf or title page.

What is the best graduation gift you ever received or gave?

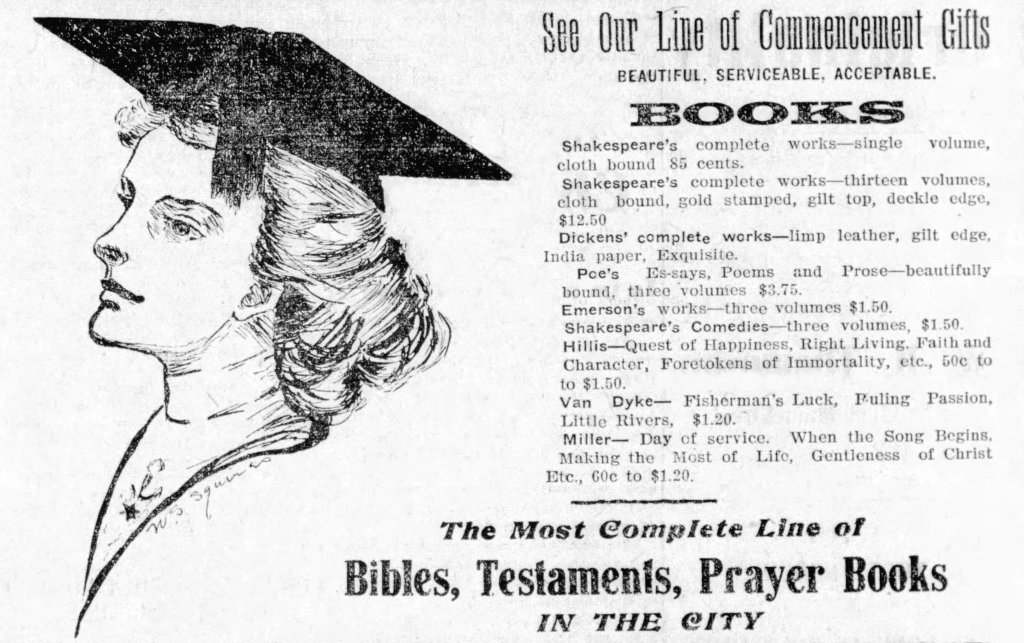

Pansy’s Easter Service

In addition to novels and short stories, Isabella Alden wrote Sunday-school lessons and programs for worship.

In 1895 she wrote a special program for Easter that was carefully crafted so it could be performed by young children, as well as older age groups.

Her Easter program included poems to read aloud, beloved old hymns to sing, and portions of Scripture to be memorized and recited.

Most importantly, the program clearly and simply related the message of Easter: that Christ rose from the dead, bringing eternal life to those who believe in him.

You can read Isabella’s entire Easter service program. Just click here or on the image below.

When I was a Girl on New Year’s Day

In 1889 Isabella wrote this charming recollection from her childhood of a very special New Year’s Day:

I close my eyes and go back in fancy to that morning long, long ago. New Year’s morning when I was eight years old.

Cold! Oh, how cold it was! Great icicles hanging from the eaves, frost covering the window-panes, snow festooning the trees and hiding the ground, and the whole air a-tingle with the music of sleigh bells. How beautiful it all was.

.

Those frosted window panes, by the way, were a source of never-ending temptation to me. I wouldn’t like to have to try to recall the number of times my fingers had to be “snapped” for forgetting that I was on no account to indulge in my favorite amusement of making “thimble chains.” I don’t quite understand what the fascination was, or is, but to this day I find it almost impossible to pass a frosted window pane, with a thimble anywhere in sight, and not stop to make just a few of those magic chains in which my childhood delighted.

.

What a pity it seemed that the contact of my chubby fingers with the clear glass should soil it, and that my mother, whose artistic taste was not so highly cultivated as mine, would not permit the amusement.

On this particular New Year’s morning the frost was unusually thick, and my sister Mary’s thimble stood on the window-seat. It was father’s warning voice that saved me, just as I was about to make a marvelous chain, which should connect two lovely frost castles.

“Take care,” he said. “Think what a pity it would be if a certain stocking which I saw hanging in the chimney corner should have to hang there all day just because a little girl forgot.”

.

I set the thimble down with an exclamation of dismay. What if I had forgotten again? Mother had decreed that the stocking, which I longed to examine, should remain untouched until after breakfast, because at Christmas time I had been so “crazy” over my presents as to be unable to eat any breakfast. For a small moment I had forgotten the stocking, though it had been on my mind all the morning, and but for father the mischief would have been done.

I went over to him to express my joy in his having saved me, and to ask him privately whether he really believed that breakfast would ever be ready and eaten and prayers be over, so I could have my stocking.

He laughed, and asked me if I supposed I would ever learn patience. “I suppose,” he said gravely, “that time will travel fast enough for you one of these days. I can remember when a week used to seem longer to me than a whole year does now.”

I exclaimed over that. I said I thought a year was a very long time indeed; that I was really almost discouraged with time, it went so slowly. I said it seemed to me that I had been waiting half a lifetime for this day to come.

He laughed again, said I was at the impatient age; then, looking serious, he repeated these lines:

“Eighteen hundred and forty-eight is now forever past: Eighteen hundred and forty-nine will fly away as fast.”

“Oh, dear me!” I said. “If it doesn’t fly faster than this has, I don’t know what I shall do. It does seem too long to wait for Christmases and New Year’s; I wish we could have two of them in a year.”

Instead of laughing at my folly, father evidently decided to give me something else to think about. He was sitting near the door of the kitchen, where my mother was at work. The kitchen walls were painted. “Mother,” he said, “may we write on the walls, since we mustn’t on the windows?”

“I should not think that would be a very great improvement on window-writing,” my mother said, but she smiled as she spoke. It was evident that it made a great difference with my mother whose plan was to be carried out; she never interfered with anything that my father chose to do. He selected from the box nearby a lovely pine board as smooth as a slate, and handed it to me.

“You may use that, and I’ll use the wall,” he said, “and we’ll see which can write our verse the quickest.”

I had been writing for two years, and prided myself on the speed and neatness of my work, but long before I had finished the lines they appeared on the wall.

“Eighteen hundred and forty-eight is now forever past: Eighteen hundred and forty-nine will fly away as fast.”

“Yes,” said my mother, pausing in her swift movements to glance at the couplet, “that it will. It has begun already; the first morning is flying too fast for me. Come to breakfast.”

I am a long while in reaching that waiting stocking, but that is to correspond with the length of time I had to wait. It seemed longer to me then than it does to look back upon it. At last the treasure was in my arms. What do you think it contained? A lovely dollie about as long as my hand, beautifully dressed, not like a fashionable lady ready for a party, but like a dear little home baby, in a long white slip frilled at the neck, precisely as my own baby slips used to be—indeed I learned afterwards that it was made from a piece of one of them. I cannot possibly make you understand, I presume, how precious that little creature was to me.

.

I suppose you are imagining a wax doll with “real” hair, and lovely blue eyes and rosy cheeks? No, she was not made of anything so cold and hard as wax. She was a rag baby—limbs and face and all—made by my mother’s own dear hand, cut from a pattern which she herself had fashioned. What a work it must have been! I never realized it until a few years ago, when I tried to cut a pattern for a dollie for my little son.

This work was beautifully done. Black eyes, my baby had, and black hair, both made carefully with pen and ink! Red checks, she had, too, and lovely rosy lips. Will you love her the less, I wonder, when I confess to you that these were made with beet juice?

.

Oh, but she was a darling! Much the most carefully made dollie I had ever owned. Heretofore I had been content with mother’s little shawl, or her long clean apron rolled up and pinned; now I had a dollie for which clothes had been made not only, but arms and feet; and actually her dress was not sewed on her, but unbuttoned and came off, and a neat little night-gown went on.

Never was I happier in my life than when I made this last crowning discovery.

I named her—you could not guess what, so I’ll tell you at once—Arathusa Angeline, and I thought the name was lovely.

“Take good care of her,” said my father, looking on with a smile of infinite sympathy, “there’s no telling what may happen to her, you know, before ‘eighteen hundred and forty-nine’ has flown away.”

.

Wishing You a Blessed Christmas

Merry Christmas!

Making Christmas Bright

Isabella Alden knew all about the Christmas shopping season. She had a large extended family, and she either bought or made gifts for each family member.

Her niece, author Grace Livingston Hill, recalled what it was like when the Aldens, Livingstons, and Macdonalds got together:

Our Christmases were happy, thrilling times. There were many presents, nearly all of them quite inexpensive, most of them home-made, occupying spare time for weeks beforehand; occasionally a luxury, but more often a necessity; not any of the expensive nothings that spell Christmas for most people today.

Isabella—being a clever and creative person—made many of the gifts she gave.

Sometimes she got gift-making ideas from magazines. She subscribed to The Ladies’ Home Journal and Harper’s Bazar, both of which regularly printed directions for making items to use or give as gifts. Sometimes she passed those ideas and directions on to her own readers.

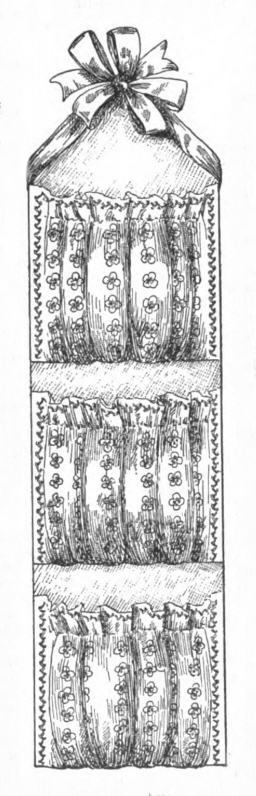

For example, an 1898 issue of The Ladies’ Home Journal published instructions for making this pretty wall pocket:

Isabella liked the idea so much, she wrote simplified instructions that children could follow and printed them in an issue of The Pansy magazine. She told her readers how to make the wall pocket from pine board, calico, buttons, and felt, and hinted it would make a lovely gift “for mamma.” She wrote:

I get the idea and most of the details from Harper’s Bazar. The article from which they are taken says the contrivance is for an invalid, but let me assure you that mamma will like it very much, or, for the matter of that, papa also.

At Christmas she encouraged boys and girls to make gifts not only for family members and friends, but for strangers, too. She wrote this to readers of The Pansy magazine:

How many Pansies are planning the Christmas gifts they will make? In all the merry bustle and happy, loving thoughts, don’t forget to throw a bit of kindly cheer into those poor little lives darkened by distress and want.

If every member of The Pansy Society would make some little gift as a loving reminder to one who otherwise would have none, how many children, think you, would be made happy?

Remember, you do it “For Jesus’ sake.”

There were instructions for making this simple knitting bag, made of fabric, ribbon, and embroidery hoops:

And this case, made from pieces of cardboard and colored ribbons, to hold photos, greeting cards, or pictures cut from magazines.

She wrote:

What a delightful present that will be when you get it done! I can imagine an ingenious girl and boy putting their heads together, and making many variations which would be a comfort to the fortunate owner.

Isabella always knew how to give those gentle reminders that children (and adults!) sometimes need about the true spirit of Christmas.

![Illustration of a pocket watch case. Above the winding stem is "14K." AS GRADUATION TIME APPROACHES - very naturally you will begin to look around for the BEST gift store. Now, the selling of Graduation Gifts is, and has long been made a specialty of by this Pfeifer Store. We have endeavored to find out what will most please a graduate, and from our personal observations we believe that many have a preferance [sic] for Watches. The following special values, therefore, will certainly be of interest at this time. FOR THE GIRL. Bracelet Watch, 7-jewel nickel movement; guaranteed. 14K solid gold, richly hand-engraved watch, Elgin movement. 14K solid gold, plain case watch, set with sparkling diamond; Elgin movement. FOR THE BOY. Elgin Watch, 15-jewel, 20-year guaranteed gold filled case. 14K solid gold watch, fitted with 15-jewel nick Elgin movement. Howard Watch, 17-jewel movement in 25-year guaranteed Elgin Howard case. ALBERT PFEIFER & BRO JEWELERS](https://isabellaalden.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/watch-daily-arkansas-gazette_sat_16-may-1914.jpg?w=709)

![Drawing of head and shoulders of four young women. WATCHES FOR THE GRADUATES. The very popular watch gift is here in a great variety of models, and at a big prince [sic] range. The gift of a "Stifft" Watch insures years of continued, satisfactory use by the recipient, and is a lasting remembrance of the all-important event - graduation. [List:] Pretty Sterling Silver Bracelet Watches; good timekeepers. Sterling Silver Braclet Watches; blue enamel inlaid. Gold Filled Bracelet Watches; guaranteed movement. Solid Gold Bracelet Watches; fine guaranteed movement. WATCHES FOR BOYS. Elgin 7-Jewel Thing Model, 20-year gold filled case. Elgin 15-Jewel Thin Model, 20-year gold filled case. "Gruen Verithin" Watches, 25-year gold filled case.](https://isabellaalden.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/watch-daily-arkansas-gazette_sat_16-may-1914_girls.jpg?w=695)

![Newspaper clipping: PANSY'S EASTER SERVICE. Superintendents and Teachers should send for a copy of the April "Pansy," now ready. It contains a beautiful Easter Service carefully arranged and prepared for Christian Endeavor societies, Epworth Leagues, King's Daughters, Mission Bands, and Sunday-schools, by Mrs. G. A. [sic] Alden, known to all Sunday-school workers under the familiar name "Pansy." An extra edition of the April "Pansy" has been issued to meet the demand created by this special Easter Service. Copies will be sent, post-paid, on receipt of 10 cents, or in quantities at seventy-five cents per dozen.](https://isabellaalden.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/from-herald-and-presbyter-1895-03-13-pg-359.jpg?w=541)