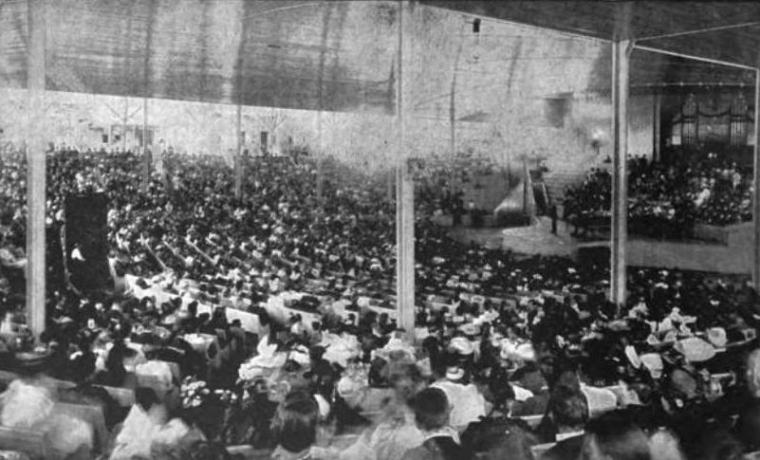

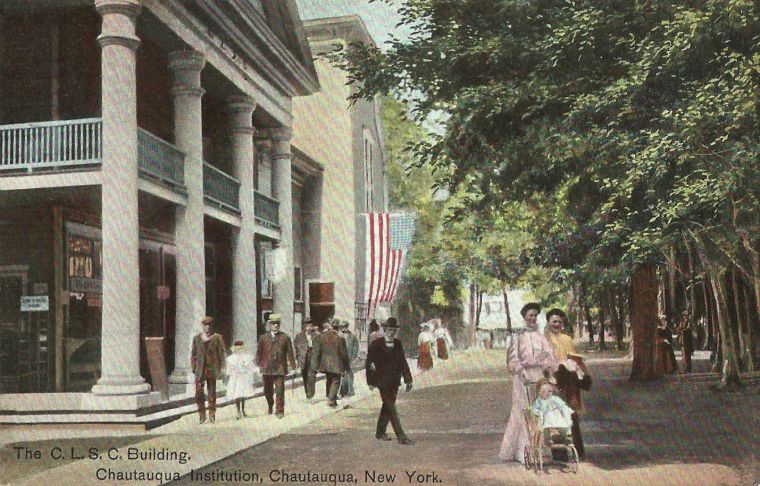

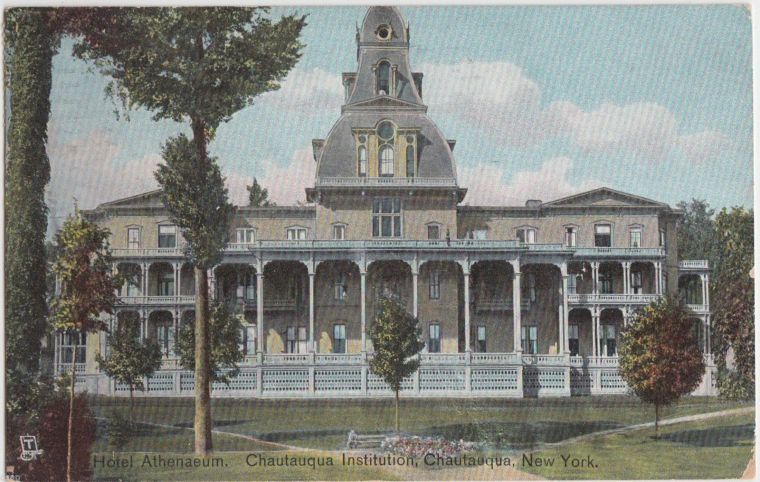

Frank Beard was one of the most popular lecturers at Chautauqua Institution. His Chalk Talk lectures drew standing-room-only crowds because of their pitch-perfect blend of humor, art and Biblical truths.

In an 1895 interview, Frank recalled how his Chalk Talks came to be:

In an 1895 interview, Frank recalled how his Chalk Talks came to be:

“I was a young artist in New York, and had just been married. My wife was an enthusiastic churchgoer; and a great deal of our courtship was carried on in going to and from the Methodist church. The result was that I struck a revival and became converted. This occurred shortly after I was married, and like other enthusiastic young Christians, I wanted to do all I could for the church.”

Soon after he joined the church, the congregation put together an evening of entertainment. The ladies, knowing of his talent, suggested that Frank draw some pictures as part of the program. Frank agreed, but he felt that just standing in front of an audience and sketching without saying anything about the pictures “would be a very silly thing.”

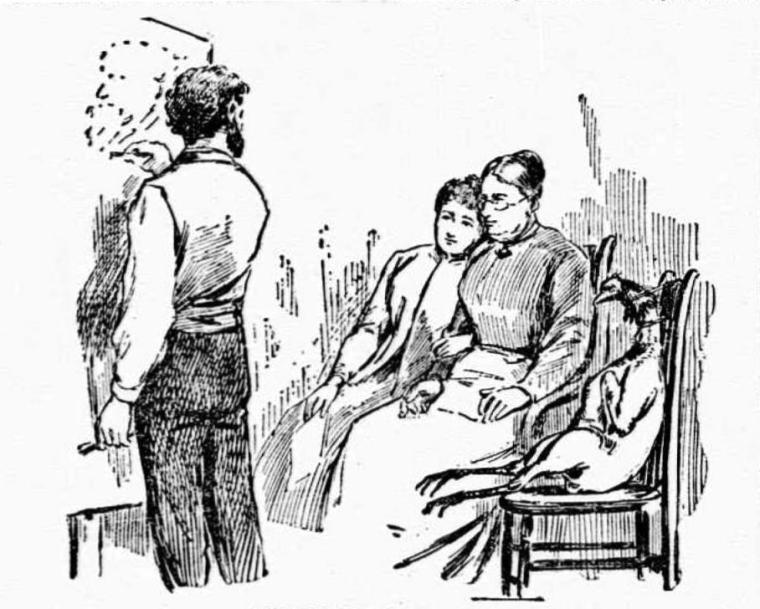

He decided instead to make a short talk and draw sketches to illustrate his points. The talk was to be given as part of a Thanksgiving celebration, and Frank later joked that he rehearsed in front of his wife, his mother-in-law, and the turkey. “Well, my wife survived, my mother-in-law did not die while I was talking, and the turkey was not spoiled.”

When he gave his talk in front of the congregation, it was a great success. Soon, other churches asked him to repeat his talk, and in very short order he had more invitations to speak than he could ever hope to accept. His wife suggested charging a fee for each lecture, hoping that the cost would deter organizations from inviting him to talk at their functions. So Frank dutifully began charging $30 per talk. The requests continued to pour in. He increased his fee to $40, then $50, but his talks continued to be in great demand.

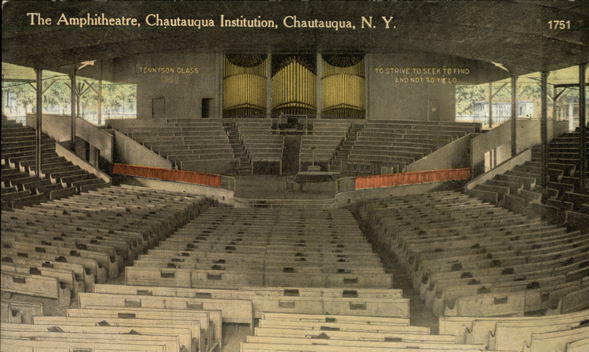

That was the birth of the Chalk Talk, and Frank soon hit the lecture circuit. He was one of the first speakers at Chautauqua Institution in New York; and he lectured at many of the daughter Chautauquas. This 1899 clipping from the Los Angeles Herald recounts Frank’s Chalk Talk at the Long Beach Chautauqua (which named July 19, 1899 Frank Beard Day):

The topics of his Chalk Talks ranged from morality tales to stories from the Bible, each told in a casual, funny, but reverent, way. He knew that people who wouldn’t listen to a “sermon” would listen to his Chalk-Talk if the truths were presented in an entertaining fashion.

In Four Girls at Chautauqua, Eurie Mitchell proved that very point. Eurie was so opposed to listening to “sermons” at Chautauqua, she refused to go to any of the lectures; but when she heard about Frank Beard’s caricatures, she decided to go see him for herself.

If you have never seen Frank Beard make pictures, you know nothing about what a good time she had. They were such funny pictures! Just a few strokes of the magic crayon and the character described would seem to start into life before you, and you would feel that you could almost know what thoughts were passing in the heart of the creature made of chalk. Eurie looked and listened and laughed.

In Isabella’s book, Frank’s Chalk Talk was able to do what no other lecture at Chautauqua could: reach Eurie’s heart and lead her, ultimately, to salvation through Christ.

“Pictures can often tell stories quicker and better than words,” Frank once said, “and I believe that cartoons can be used in the service of religion, righteousness, truth, and justice.”

To prove his point, he once asked, “If you were commissioned to teach a child the nature of a circle, would you begin by stating that a circle is an area, having for its center a point, and bounded by a circumference in the nature of an endless imaginary line, which at all points is at an equal distance from the center? No! You would do nothing of the sort, but you would [show] its nature and properties [by drawing a circle] in black and white.”

Sometimes the subjects of his Chalk Talks were very simple. He told a story, for example, of how a blackboard and chalk could be used to teach a Sunday-school class of young children who had never before seen the Christian symbol of a cross inside the shape of a heart. He started by drawing the simple outline of a heart on the blackboard.

“A heart!”

“Yes, a heart. Now, I mean this to represent a particular heart—I mean it for my heart. What is it now?”

“Your heart!”

“Don’t forget that. Now, see what else I will draw.” And he drew a child’s face within the heart.

“Now what have I made?”

“A little boy!” “A little girl!” “A little child!” Variously cried the children.

“A little boy!” “A little girl!” “A little child!” Variously cried the children.

“Yes, a little child; but where is the child?”

“In the heart.”

“In the heart?”

“In your heart.”

“That’s right. Now, what does it represent? When I tell you that I have a little child in my heart, what does it mean?”

“You mean you love the child.”

“You mean you love the child.”

“Exactly. Now I will rub out the child and put a cross in the heart. What does that mean?”

“You love the cross.”

Then he went on to explain in a simple way what loving the cross meant.

He also shared an example of one of his lessons for older children and adolescents. He used this lesson to illustrate the concept of the narrow Christian path described in Matthew 7:13-14:

A young man is attracted by the appearance of beauty and the pleasure along the broad way. Timidly at first, for he is not bad and rather fears evil—but he loves play and pleasure—so he steps into it. He knows it is not the right way to take but he thinks to himself:

“After a while, after I have had a good time, I will go over to the right path and come out all right after all.”

Frank went on to explain how the young man fell in with evil companions and was drawn further away from the good path.

The young man learned to smoke and chew tobacco and read books “which mislead and give us wrong notions in life, that make heroes of scamps, thieves and liars.”

As Frank continued the lesson, he amended and enhanced his original drawing to show the progressive results of the choices the young man made in his life.

Wherever he gave his Chalk Talks, he was well received, and his reputation grew. But not everyone was a fan of using a blackboard and chalk as teaching tools in the Sunday-school. Frank shared a story about one church that decided to use a man in their congregation—they assumed he had talent because he was a sign painter by profession—to illustrate Sunday-school lessons. The man decided to illustrate the story of Samuel as a child, entering the apartment of the high priest Eli in answer to his summons. His efforts were not well received.

“Some objected to the bed-posts,” Frank said. “Some didn’t exactly know why, but the drawing didn’t conform to their idea of Samuel at all, and, more over, Eli’s nose was out of proportion.”

The man’s next attempt didn’t fare any better, when he drew Goliath about thirty-five feet high in proportion to David. In fact, the congregation didn’t like anything at all about the poor sign-painter’s efforts at the blackboard.

Isabella Alden’s book Links in Rebecca’s Life featured a character who also disliked Chalk-Talk style lectures. She was a Sunday-school teacher who hated chalk and blackboards.

“They are such horrid dusty things. You get yourself all covered with chalk, and just ruin your clothes. I can hardly wear anything decent here as it is. If I had a blackboard, I should give up in despair.”

“I should think it would be a great help in teaching children,” Rebecca said.

“Well, I don’t know. What could I do with it? I don’t know how to draw, and as for making lines and marks and dots, I am not going to make an idiot of myself. What’s the use?”

But Frank Beard believed no special talent was required for a teacher to incorporate chalkboard drawings into Sunday-school lessons.

“Many are apt to think some extraordinary genius is necessary to fit a teacher to use the blackboard,” he said. “It is a mistake. You can teach better with a pencil than without. You can learn to draw far better than you ever imagined possible.”

In 1896 Frank published a book for Sunday-school workers; in it he gave simple instructions for using the blackboard to illustrate Bible lessons.

His book included how-to’s on perspective, lettering, and using easy-to-draw symbols as illustrations. Here are some of the symbols he illustrated:

The purpose of writing the book, he said, “is to show how the blackboard can be used in the Sunday-school, and to furnish such instruction in drawing upon it” so it can be done in the most effective way.

He was quick to say that he didn’t want the blackboard to monopolize the Sunday-school or supplant other useful forms of instruction. But, if used correctly, Frank Beard proved that the blackboard—and Chalk Talks—could be the “instrument which proves effective as a means of winning souls to Christ.”

In 1895 Frank Beard gave an interview to the Washington D.C. newspaper The Evening Star. Click on this image to read the interview in which Frank tells how he invented the Chalk Talk:

In 1895 Frank Beard gave an interview to the Washington D.C. newspaper The Evening Star. Click on this image to read the interview in which Frank tells how he invented the Chalk Talk:

.

.

Click on the book cover to learn more about Links in Rebecca’s Life.

Click on the book cover to learn more about Links in Rebecca’s Life.

.

.

Click on the book cover to learn more about Four Girls at Chautauqua.

Click on the book cover to learn more about Four Girls at Chautauqua.

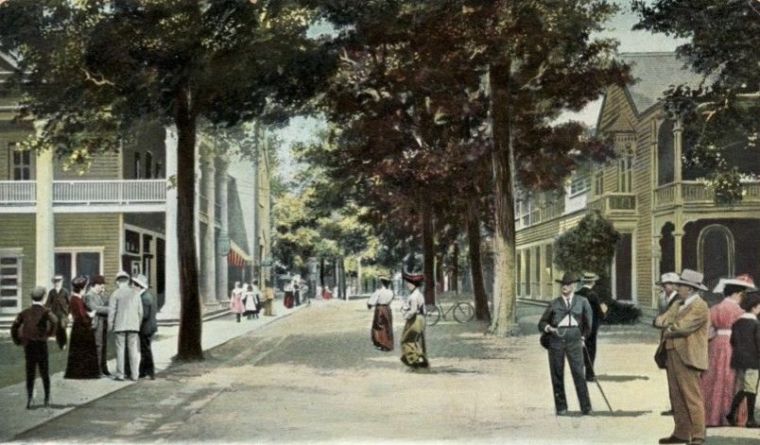

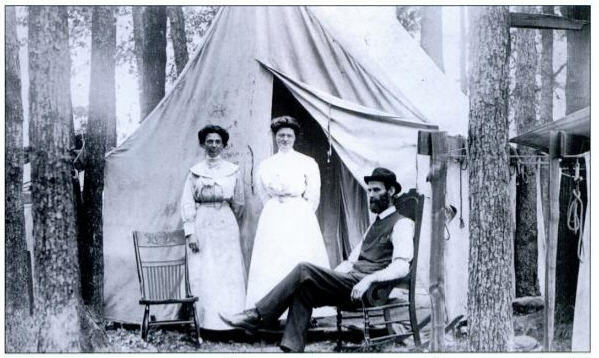

The Chautauqua Institution kept things running in a timely manner. Five minutes before the hour a bell rang, giving notice that the next event or class would begin promptly at the top of the hour. The sound of the bell usually resulted in a throng of people streaming out the door of one class in order to get to the next class on time. Bells marked the hour until 10:00 p.m. when the last night bell rang signaling quiet.

The Chautauqua Institution kept things running in a timely manner. Five minutes before the hour a bell rang, giving notice that the next event or class would begin promptly at the top of the hour. The sound of the bell usually resulted in a throng of people streaming out the door of one class in order to get to the next class on time. Bells marked the hour until 10:00 p.m. when the last night bell rang signaling quiet.

1 the Miller Bell Tower was erected alongside the dock. It was built to commemorate the life and contributions of Chautauqua co-founder Lewis Miller. When the girls returned in 1913 (as described in Isabella Alden’s book, Four Mothers at Chautauqua), they would have seen the beautiful new bell tower as they approached the dock; and they would pass it as they stepped off the boat and entered the Institute grounds.

1 the Miller Bell Tower was erected alongside the dock. It was built to commemorate the life and contributions of Chautauqua co-founder Lewis Miller. When the girls returned in 1913 (as described in Isabella Alden’s book, Four Mothers at Chautauqua), they would have seen the beautiful new bell tower as they approached the dock; and they would pass it as they stepped off the boat and entered the Institute grounds.