Isabella Alden was a teacher at heart. Before she became a bestselling author, she earned her living as a schoolteacher and devoted countless hours to preparing meaningful Sunday school lessons for her students. So when the Chautauqua movement began in the early 1870s, it was a natural fit—she was involved from its earliest days.

The Chautauqua idea started simply enough as a summer gathering where Sunday school teachers could learn best practices for their work and enjoy a bit of recreation when classes weren’t in session.

What began as a “Sunday School Assembly” in 1872 gradually evolved into something much bigger—a “summer university” that welcomed people of all incomes, backgrounds and education levels. It was, wrote Harper’s Monthly Magazine in 1879, “a school for those who, conscious of their need, earnestly desire the highest culture possible for them.”

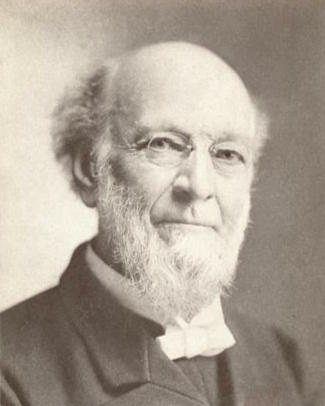

One of Chautauqua’s founders was Rev. Dr. John H. Vincent, who served as Sunday school secretary of the Methodist Episcopal Church and was a close friend of Isabella’s. Like her, he prized knowledge, learning, and mental discipline.

But what really united them was their shared conviction: that it was possible—even essential—to study art, science, literature, and history through the lens of religious truth.

In 1909 Rev. Vincent addressed the Chautauqua Women’s Club on a topic close to both his and Isabella’s hearts: the importance of education in religious experience. Fortunately, his speech was preserved in an issue of Chautauqua Herald, the assembly’s monthly newspaper.

In many ways, his thoughts on balancing education with Christian faith feel remarkably relevant today—more than a century later. Below are some key points that illustrate the heart of his message. See if you agree with his ideas.

“The Educational Factor in Religious Experience.”

Education and religion used to be too separated. But that is not the case in our time.

In our time education and religion are drawing closer together every day, and one sign of our progress is the growing recognition of religious teaching. I believe that people will increasingly see the value in religious teaching as it becomes purer and freer from the bigotry that once characterized it.

We all remember when fanaticism, bigotry, and opposition to science (as if science were opposed to religion!), found theirplace in the church and prejudiced the minds of scholarly people. As we broaden our perspective and gain a wider view of the world of Nature, this fanaticism is dying out and the scholars and the religious teachers are no longer enemies.

Religion opens the whole field of education, in which theology is fundamental. Religion in its truest sense is education.

Educated people ought to be religious. Religious people ought to be educated. When we surrender our intellect to God through religion, He returns it to us as a precious gift to use. Let us, then, as a form of religious expression, learn how to think—and delight in it.

There are seven points in the consideration of religious life as related to personal culture.

First, religious experience and personal growth work together by developing power of thought.

Second, we should cultivate our ability to reason. Let us ask, why is this? and, why is that?—applying our reasoning not only to intellectual pursuits, but to the realities of daily life.

Third, religion is a great thing to cultivate imagination, and we must develop imagination if we want to broaden our lives. But we must also keen imagination in check.

Thought, reason, imagination—these are all effects of religious experience.

Fourth, we should identify a noble, guiding purpose in life. What am I living for? That is the question we should ask ourselves. How can I beautify my little corner, and how can I do good to my neighbor? Why, every line I read or word I speak leaves its mark on some other human being. Men and women can sink to a lower level very easily. It is a great thing when one woman influences to higher thought one man or ten men.

Fifth, religion should help us see ourselves accurately—not too high, not too low.

Sixth, let us remember that a genuine religious spirit combined with the pursuit of learning will develop philanthropy—a pure philanthropy rooted in Christian values.

And seventh, let us remember that religion develops character. Practice builds virtue—the hallmarks of character that Peter describes when he says “add to your faith courage—add to your faith integrity—add to your faith strength.” Peter understood the secret of inner spiritual life.

“Add to your faith virtue, and to virtue knowledge, and to knowledge moderation, and to moderation”—patience, strength—“godliness, and to godliness, brotherly kindness, and to brotherly kindness charity. For if these things be in you and abound, they make you that you shall neither be barren nor unfruitful in the knowledge of our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ.” (2 Peter 1:5-8)

Religion thus becomes a process of self-mastery in which we take time to focus our abilities and develop them.

Rev. Vincent’s speech captured so much of what Isabella believed and practiced throughout her life. She never saw a conflict between being educated and being faithful. Her novels explored complex themes and moral questions. The articles she published in The Pansy magazine taught children about science, geography, and literature—all while maintaining a foundation of Christian values. Like Rev. Vincent, she understood that true education develops the whole person: mind, character, and spirit. It’s a vision of learning that, at the time, was both revolutionary and deeply needed.

What do you think?

Is it possible to pursue knowledge while maintaining spiritual grounding?

Can we cultivate our minds without losing our moral compass?

Dr. Vincent and Isabella would say yes. And given the lives they both lived—dedicated to learning, service, and faith—their example suggests they might be right.