It’s autumn in the United States, and for most Americans, that means shorter days and colder temperatures.

It also means the start of the flu season, when about 20% of the population can expect to suffer feeling feverish, achy and just plain crummy for about a week between now and April of 2018.

Influenza season was troublesome in Isabella’s time, too; especially because Americans didn’t have the advantage of the flu vaccines and anti-viral drugs we have today.

But in 1918, when Isabella was 77 years old and living in Palo Alto, California, Americans suffered through a terrifying epidemic of influenza known as the Spanish Flu.

.

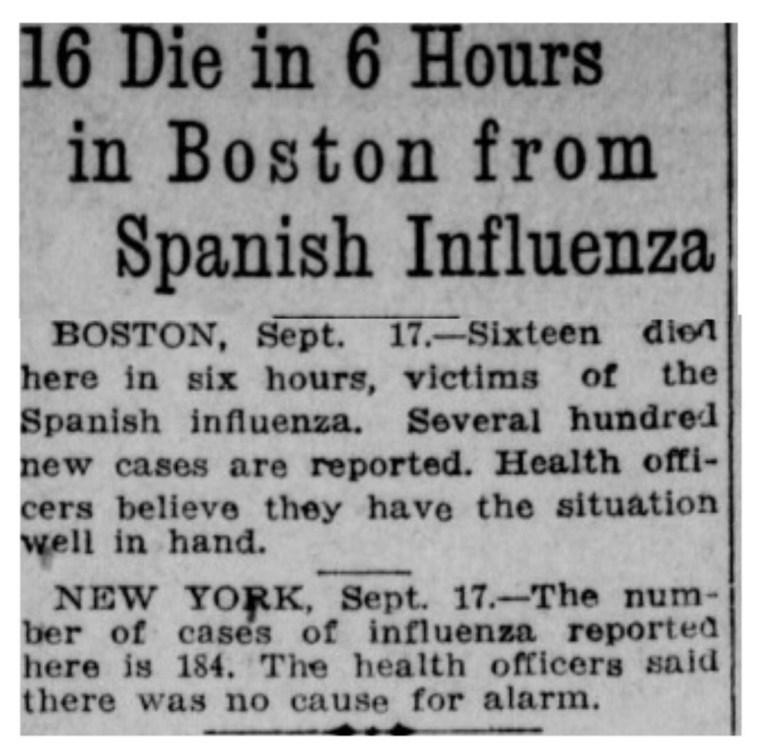

The first documented wave of Spanish Flu struck the U.S. with a vengeance in the fall of 1918. Americans quickly realized this strain of flu was not the usual variety that brought chills, fever and fatigue that lasted a few days.

This new strain of flu was highly contagious, and it proved particularly fatal to healthy young adults—an alarming complication. Previous strains of flu usually resulted in death for children and the elderly; and health officials were baffled by the fact that the healthiest segment of the population seemed to be the most vulnerable.

.

Another terrible consequence was the speed with which the flu struck. Victims died within hours or days of their symptoms appearing. In fatal cases, the victims’ skin turned blue and their lungs filled with fluid; nothing could be done to save them.

The first wave of the epidemic struck the eastern part of the United States hard.

.

Large cities, small towns, and rural areas suffered equally. One physician at an Army station in Massachusetts wrote:

“These men start with what appears to be an attack of la grippe or influenza, and when brought to the hospital they very rapidly develop the most viscous type of pneumonia that has ever been seen. Two hours after admission they have the mahogany spots over the cheek bones, and a few hours later you can begin to see the cyanosis extending from their ears and spreading all over the face, until it is hard to distinguish the coloured men from the white. It is only a matter of a few hours then until death comes, and it is simply a struggle for air until they suffocate.

“It is horrible. One can stand it to see one, two or twenty men die, but to see these poor devils dropping like flies sort of gets on your nerves. We have been averaging about 100 deaths per day, and still keeping it up. There is no doubt in my mind that there is a new mixed infection here, but what I don’t know.”

In very short order, hospitals were overrun with patients. Health officials had to commandeer meeting halls, golf courses, large private homes, and any other places that could be converted into temporary hospitals to house victims of the epidemic.

.

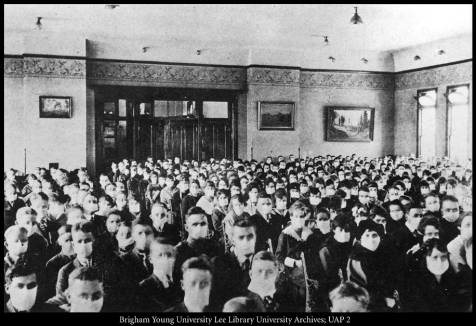

In some towns officials shut down all public places, including schools and churches, and ordered citizens to wear masks at all times.

.

The numbers of fatalities increased steadily. In some places entire families were wiped out. Physicians, nurses, and healthcare workers couldn’t keep up with the numbers of patients that needed their care, and they soon became patients themselves. By October 1918 New York City’s health department estimated that over 20% of the city’s nurses were sick.

Mortuaries were also overwhelmed; bodies piled up. Morticians and cemetery workers were struck down with the flu like everyone else, and some communities had to resort to disposing of bodies in mass graves. In other places, grieving family members had to dig graves for their own loved ones.

.

Entire cities came to a virtual halt; so many people were ill there was no one to deliver mail, collect garbage, or harvest crops. Businesses closed and government agencies shut down because there was no one well enough to report to work.

.

Health officials and town leaders fought against the disease in the only ways they knew how. They told citizens to stop shaking hands. They ticketed anyone who coughed or sneezed or spat in public.

.

They closed theaters and barred libraries from circulating books.

They passed ordinances prohibiting people from gathering, hoping to stop the virus from spreading.

.

Some cities required residents to wear masks any time they stepped outside the doors of their homes.

Meanwhile, residents in mid-west and west coast states of the country—such as in California, where Isabella was living at the time—could do little more than hope the deadly epidemic would remain confined to the east coast.

.

Their hopes were bolstered by uninformed health officials who, in an effort to keep the public calm, spread incorrect information about the deadly virus.

.

But in truth, mid-west and west coast states could do little to halt the epidemic’s march toward their cities and towns.

.

It didn’t take long before the first confirmed cases of Spanish Flu were reported in Northern California.

.

In the Santa Clara Valley, where Isabella lived with her husband and family, the first documented cases of Spanish Flu hit in November, 1918.

County officials and town leaders imposed quarantines and prohibited residents from congregating, hoping to stop the spread of the virus.

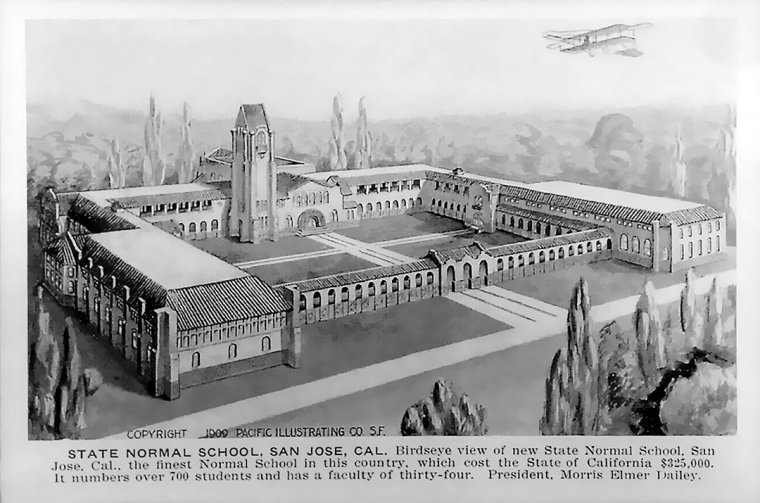

Like other places in the country, Isabella’s neighborhood hospitals were soon over-crowded with patients. Health officials cancelled all school classes and converted the newly-built San Jose Normal School into hospital wards.

.

By the time the epidemic ran its course in the spring of 1919, fifteen residents of Isabella’s community had died, and over 300 had been infected.

.

The impact of the flu on the country was staggering. One out of every four Americans had been infected by the time the Spanish Flu epidemic ran its course in 1919. Over 550,000 Americans had died, and more than 50 million people worldwide were killed.

Isabella’s family was spared. While she and her family may have taken ill, no members of the Alden or MacDonald families died from the Spanish Flu. Still, it must have been a frightening and anxious time for Isabella, as it was for all Americans.

Here’s a brief video that explains the impact the Spanish Flu had on residents of South Carolina, especially its small communities, like Isabella’s:

And this video (from PBS’s American Experience series) includes interviews with Americans who survived the epidemic and give first-hand accounts of its impact on their families and neighborhoods:

What a terrifying illness! I have heard bits and pieces about the Spanish flu, but your complete report brings it all together. As always, wonderfully done! Karen

Thanks, Karen! I think Isabella and her family were extremely blessed to have survived those frightening times unscathed. —Jenny

I think the scariest part of that is how swiftly it struck and killed its victims. I never knew! You could literally be healthy in the morning and dead by nightfall! Terrifying. I wonder how anyone survived at all?

I have been told my husband’s aunt, a beautiful girl with long auburn hair died of this flu in 1918.

So sad, isn’t it? I wonder if my daughter’s namesake Great Aunt Naomi (who died at 21 in 1900’s) may have died of this, too?

I found this post while doing a reverse image search for that photograph you included in your post of that family and their pet cat who are all wearing masks.

Do you have any information about who that family was or what happened to them? I’m so curious. 🙂

I’m afraid I don’t have any additional info on the people in the photo, Lydia. Like you, I wish I knew what happened to them! I found the photo on Calisphere.org, which lists Dublin Heritage Park and Museums as the contributor of the photo. Sounds like there’s a chance the family in the photo was located in Dublin (or the Oakland bay area) of California. I hope that helps! -Jenny