Isabella Alden never actually said so, but there’s an argument to be made Flossy Shipley Roberts may very well have been her favorite character. Of all the characters Isabella created, Flossy made the most appearances in her novels.

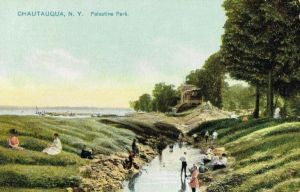

Flossy first appeared in Four Girls at Chautauqua. She was also a key character in The Chautauqua Girls at Home, Ruth Erskine’s Crosses, Four Mothers at Chautauqua, and Echoing and Re-echoing.

And while she was only mentioned in Judge Burnham’s Daughters and Ruth Erskine’s Son, Flossy made her final appearance—and played a major role—in Ester Ried Yet Speaking.

Perhaps one reason Flossie was so well-loved—by Isabella and by her readers—was that she was honest and truthful, yet deceptively strong. People constantly underestimated Flossy because she was soft spoken and was willing to please others.

But Flossy also had a strong moral sense of right and wrong. She relied on her Christian faith to give her the strength she needed to always do right rather than what others wanted her to do.

She was also kind hearted, especially when it came to children. Flossy was just as willing to teach a Sunday school class full of ragged orphaned street boys as she was to serve tea on her best china to a wealthy church deacon and his wife.

That was the case in Esther Ried Yet Speaking, when Flossy took on the task of teaching a Sunday-school class of rough street boys. During the first class, Flossy took an interest in one of those boys, Dirk Colson and his sister Mart. In the story, Flossy’s concern for them and the rest of the boys—and the actions she took to help them—reflected Isabella’s own principles.

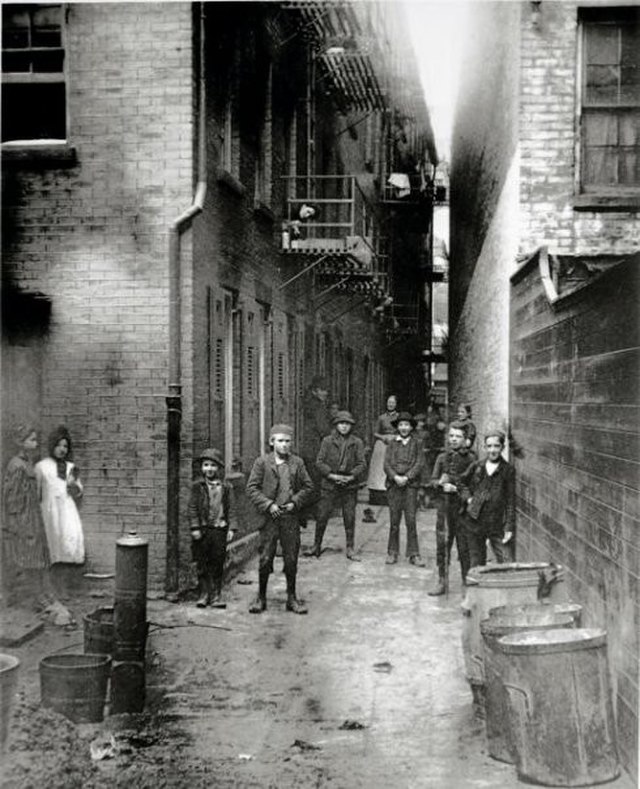

Isabella was keenly interested in the problem of street children living in large urban areas like New York City. In 1889 she wrote:

There is, in New York City, a meeting known as the “Woman’s Conference.” On the second Friday of every month they meet together to discuss matters of importance and see what they can do to help along the good work which is being done in this world. A few weeks ago they took for their subject the “Street Children’s Sunday,” their object being to see what they can do to help these miserable, neglected, almost forgotten, children to something better than their sorrowful lives have yet known.

The Sun (a New York newspaper) covered that women’s conference and published an account of the meeting, including this paragraph:

At the meeting, which was presided over by Mrs. Lowell of the State Board of Charities, Mrs. Houghton, literary editor of the Evangelist, introduced a subject of the Sunday Life of tenement-house children, a large class of whom do not attend the Sunday schools, and whose Sundays, owing to the drunkenness of their parents, which is more general on that day than any other, and also to the overcrowding of the small rooms in which they live by the presence of the entire family on that day, are full of wretchedness and discomfort. “The children do not laugh enough,” Mrs. Lowell said. “They did not know how to play or to be happy.” This subject has been long of great interest to Mrs. Houghton, and out of this discussion germinated a plan to do something for those little wretched waifs of humanity to brighten their lives, and ultimately to make of them better men and women and more intelligent and worthy citizens.

Isabella strongly believed in the last line of the article: that making the lives of poor boys and girls better will ultimately help them grow to be better men and women.

She also had the example of Jacob Riis, a newspaper reporter who documented living conditions in New York slums. Through his written articles and photographs, he almost single-handedly educated Americans about the necessity of better living conditions for the poor. He advocated for clean drinking water, public parks, and child labor laws, and he was instrumental in implementing these and many other reforms in New York City. Riis and Isabella both attended Chautauqua Institution at the same time, and Riis was close friends with Bishop John Vincent, one of Chautauqua’s co-founders.

Isabella may very well have been thinking of Riis when she wrote about Flossy’s efforts to reach and influence the street boys in her Sunday-school class.

In one scene, Flossy gets lost in the slums while trying to visit Dirk, and a street boy named Nimble Dick helps her find Dirk’s house.

Mrs. Roberts uttered an exclamation. The house was one of the most forlorn in the row, seeming, if the miserable state of the buildings would admit of comparison, to be more out of repair than the others. It came home to her just then, with a sudden, desolating force, that human beings such as she was trying to reach, and such as she hoped would live in heaven forever, called such earthly habitations as these homes. What possible idea could they ever get of heaven by calling it “home”?

“Do they have the whole of the house?”

She asked the question timidly, for the building looked very large, but she was utterly unused to city tenement life.

“The whole of that house?” Dick fairly shouted the sentence, and bent himself double with laughter. “Well, I should say not, mum! As near as I can calculate, about thirty-five different families have that pleasure. The whole of the house! Oh, my! What a greeny!” And he laughed again.

Mrs. Roberts exerted herself to laugh with him, albeit she was horror-stricken. Thirty-five families in one house! How could they be other than awful in their ways of living?

“I know almost nothing about great cities,” she said. “My home was in a much smaller one.”

This was the truth, but not the whole truth. Instinct kept this veritable lady, in the truest sense of the word, from explaining that she knew nothing about the abject poor, when she was speaking to one of their number.

But Flossy quickly set about learning all she could about Dirk, his sister, and their neighbors because she felt a distinct calling to help them. When she returned a second time to Dirk’s tenement building—this time accompanied by her husband—other residents of the tenement warned her to stay away from Dirk.

It was strange, she could not herself account for it; but with every added word of misery that set poor Dirk Colson lower and lower in the scale of humanity, there seemed to come into this woman’s heart, and shine in her face, an assurance that he was to be a “chosen vessel unto God.”

To Flossy, helping Dirk and the rest of “her boys” was essential. And when someone tried to change her mind by asking what good Flossy could possibly do for such creatures, she replied:

“Don’t you think that Jesus Christ died to save them? And don’t you think he wants them saved? And will he not be pleased with even my little bits of efforts if he knows that my sincere desire is to save these souls for his glory?”

Her “little bits of efforts” may seem small at first, but Flossy soon begins to see results with “her boys.”

You can read all about the plan Flossy came up with, and how the boys responded, in Isabella’s novel, Ester Ried Yet Speaking.