Have you ever wondered what it would be like to be famous?

Imagine walking into a room filled with people who burst into applause as soon as you enter. Then imagine that you’ve agreed to speak at an assembly that’s filled to overflowing with people, seated and standing in every available space, who hang on your every word.

That’s a little taste of what life was sometimes like for Isabella Alden. Today it might be hard for us to understand just how famous and beloved she was by people across the country. In a time before social media, television, and radio, Isabella had a nation-wide reputation as both an author and as a respected and knowledgeable public speaker on a variety of topics, including the development of Sunday-school lessons.

In 1886 Isabella and her husband, Rev. G. R. Alden, were living in Cleveland, Ohio, where Rev. Alden was pastor of a Presbyterian church. But when he wasn’t preparing sermons, and she wasn’t writing novels and stories for Christian magazines, the Aldens traveled the country to help churches design and implement well-organized, robust Sunday-school curriculums.

In June of that year they were invited to attend a conference in Wellington, Kansas, where the local churches hoped to find a way to better manage their Sunday-school offerings to children and adults. The Aldens accepted.

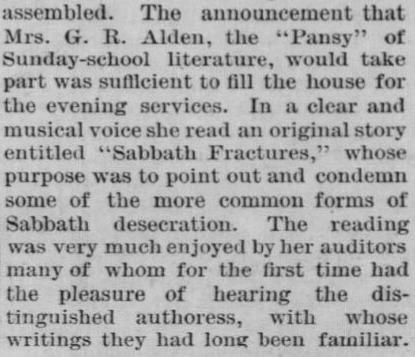

As soon as the local newspapers announced that Isabella Alden would be among the featured speakers, the churches were guaranteed to have an excellent turnout for their conference.

Here’s how the local newspaper described the scene on the first night of the conference when Isabella made her appearance:

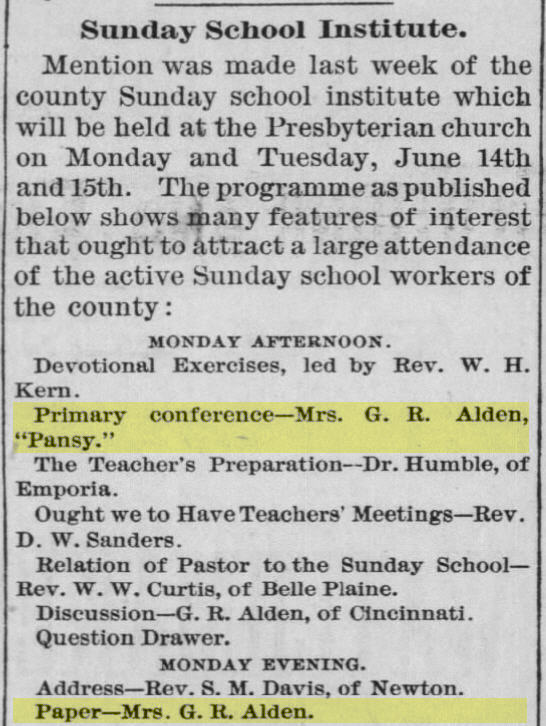

The meetings began on a Monday afternoon and Isabella took an active role, according to the agenda:

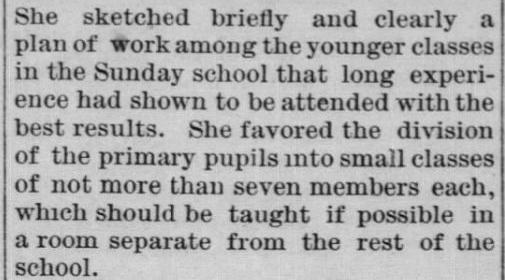

In one of the sessions she spoke about how to design Sunday-school lessons for children in the Primary Class age range of four to eight years:

In another session she participated in a discussion on the proper way to prepare teachers for the work of teaching meaningful lessons:

On Monday evening she read one of her short stories, “People Who Haven’t Time and Can’t Afford It,” which, the newspaper reported, “held the close attentions of the audience in spite of the discomforts of the crowded room.”

The rest of the conference was similarly busy for Isabella. The last night of the conference was “attended by an audience larger than the seating capacity of the church.” Isabella closed the evening session by reading a paper she wrote about “the Penn Avenue Church” and the difficulty the church had raising money for Sunday school purposes and for books to stock a small church library.

Eventually, Isabella revised that “paper” into a short story called “Circulating Decimals,” which was published two years later.

By every measure, the 1886 Sunday School Institute in Wellington, Kansas was a resounding success.

And with Isabella’s many contributions—from offering practical advice to reading stories with a message—it truly was a “feast of good things.”

One final note:

Isabella may have been a famous celebrity, but when she and Reverend Alden made these trips, they rarely stayed in a hotel. Instead, they were usually invited to stay in the home of one of the local church members. In Wellington, Kansas, they stayed in the home of George and Laura Fultz. Mr. Fultz was a leading businessman in Wellington, and he and his wife were active members of the Presbyterian church.

How lucky were Mr. and Mrs. Fultz! Isabella and her husband stayed with them for five nights. Imagine having your favorite author sit at your dinner table, join you in a morning cup of coffee, or share an evening on your front porch, relaxing and watching the sun set together after a full day of meetings.

If you were fortunate enough to have Isabella as a guest in your home, what kind of questions would you ask her?

All of the short stories mentioned in the post are available for you to read for free. Just click on any of the highlighted titles or cover images to download your copy from Bookfunnel.com.

![Newspaper clipping: The committee in charge of the arrangements make this further announcement: “We desire again to call the attention of all parents, Sunday School workers, and especially all young people, to this unlooked for opportunity to meet and greet Mrs. G. R. Allen [sic], “Pansy.” She is known and loved as the author of such helpful and thrillingly interesting books as “Ester Ried,” “Four Girls at Chautauqua,” “The Hall in the Grove,” “One Commonplace Day,” etc. Her engagement with the State Sunday School Assembly at Ottawa, Kansas, brings her west at this time and we trust that a “crowded house” will show our appreciation of the extra effort she is making to come to Wellington. The other speakers from abroad, and those among us who have kindly agreed to assist in these meetings, will give us a feast of good things. Come everybody and enjoy the feast.](https://isabellaalden.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/06-11-05.jpg?w=544)

![“PANSY” ON CHURCH SOCIETIES.

Mrs. Alden and the Adelbert College Glee Club Entertain an Audience.

A plainly attired lady of medium hight [sic] wearing a brown dress and lace collar, was introduced to a large audience at the Case avenue Presbyterian church last evening as Mrs. G. R. Alden, or the first “Pansy” of the season after an unusually severe winter.

Mrs. Alden, who is well known in the literary world as “Pansy” the Sunday school workers’ favorite authoress, read several chapters of her republished book “Circulating Decimal,” to the great delight of her hearers. She is a pleasing and natural reader, and knows how to interest an audience. She read of the trials and tribulations of Sunday school societies, described the efforts of the young ladies to “get up” a church fair and the cantata of “Esther,” how they quarreled over the leading parts and how they netted the enormous sum of $19.02

In the course of the evening the Adelbert college glee club entertained the audience with several excellent selections, capitally sung, among which were “Nellie was a Lady,” “Way Down Upon the Suwanee river” and “George Washington.”](https://isabellaalden.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/plain-dealer_cleveland-oh_1885-04-15_page-8.png?w=716)